By Rocco Praderio

In the fall of 1989, thirty-five-year-old visual artist and writer David Wojnarowicz had enough to worry about. One year earlier he had tested positive for HIV and was subsequently diagnosed with AIDS. The new antiretroviral treatment that he had been taking made his mind race and caused frequent spells of nausea and vomiting. On top of that, Wojnarowicz was still grieving the loss of his partner, the photographer Peter Hujar, whom he had tirelessly cared for as the same novel virus quickly extinguished Hujar’s life.

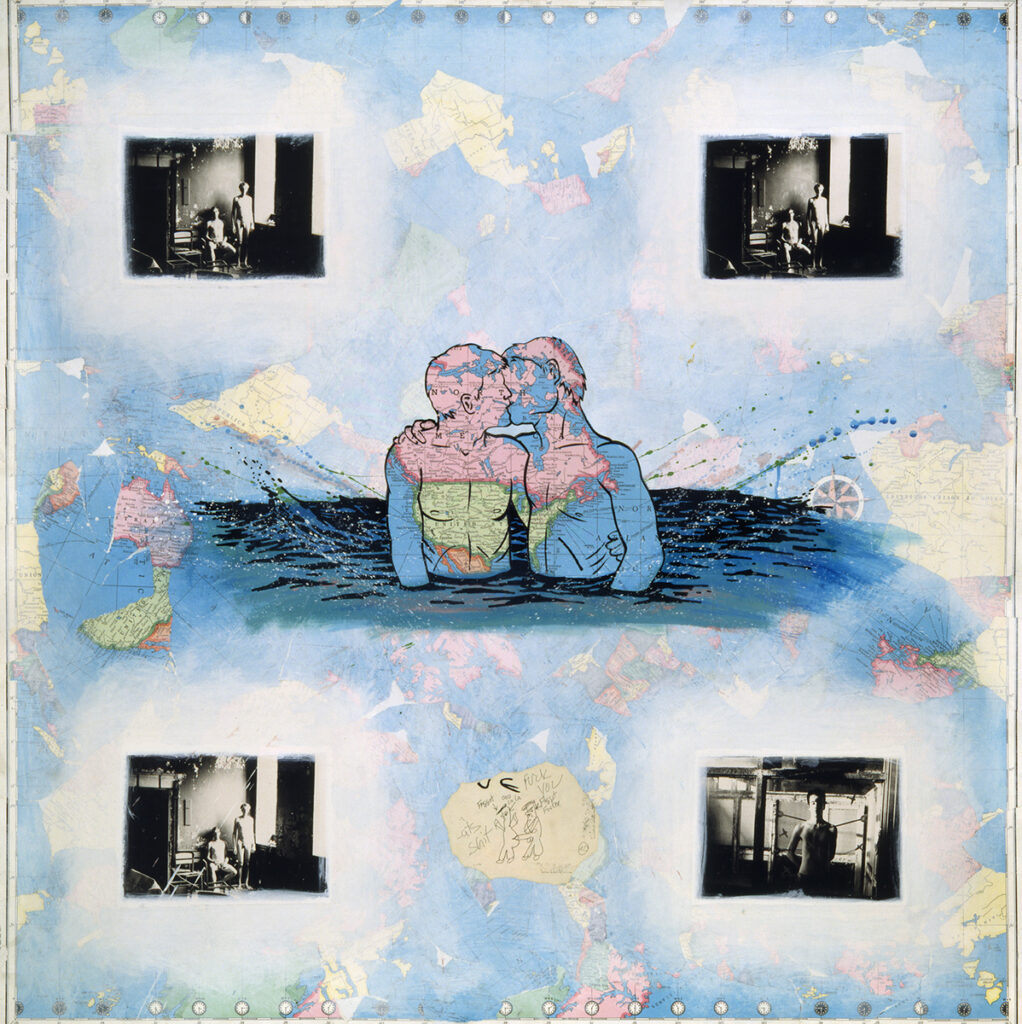

Wojnarowicz (pronounced voy-nəh-ROH-vitch) had also been deflecting nervous phone calls from Susan Wyatt, the executive director of Artists Space, a small nonprofit gallery tucked away on Cortlandt Alley in lower Manhattan. Artists Space was preparing to open an exhibition called Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, curated by the photographer Nan Goldin, who wanted to highlight the devastating effects of the ongoing AIDS crisis on the arts community. Goldin asked Wojnarowicz to participate in the show and he agreed, submitting both a handful of photographs as well as an essay for the exhibition catalogue titled Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell. Like all Wojnarowicz’s work, his essay was biting and incisive, criticizing the lackluster and often homophobic responses to the AIDS crisis from the government and religious establishment.

“At least in my ungoverned imagination I can fuck somebody without a rubber or I can, in the privacy of my own skull, douse Helms with a bucket of gasoline and set his putrid ass on fire or throw Rep. William Dannemeyer off the Empire State Building. These fantasies give me distance from my outrage for a few seconds.” It was this deadpan daydream of violence against Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina and House of Representatives Member William Dannemeyer of California, included in his essay, that landed Wojnarowicz in hot water with Wyatt and the board of Artists Space. He insisted on calling out Helms and Dannemeyer in his essay for two reasons: not only had these politicians led national campaigns against gay rights and AIDS crisis relief, but they also continuously attacked the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for funding projects they found personally objectionable. The text also singled out the Catholic Archbishop of New York, Cardinal John O’Connor, describing him as a “fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas up on fifth avenue,” for the Cardinal’s superficial commitment to AIDS crisis relief as the church refused to endorse condom use and fought against safe sex education and abortion access. Despite Wyatt’s anxious requests to tone down his essay, Wojnarowicz refused.

On the morning of November 8th, 1989, Wojnarowicz left his loft in the East Village to buy a copy of the New York Daily News. He was expecting the paper to be dominated by coverage of the landmark election of David Dinkins as the first Black mayor of New York City, which had occurred the night before. However, he was shocked to see the headline “CLASH OVER AIDS EXHIBIT: SoHo gallery fears Fed backlash” on the front page—and to read that his catalogue essay was the primary reason why the National Endowment for the Arts would be rescinding its grant to Artists Space to support the exhibition.

It is rare that matters of cultural policy make front-page news in the U.S., but Wojnarowicz’s work had become a lightning rod overnight in the burgeoning American culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. By this point, Wojnarowicz was already known for his unabashedly visceral artistic practice, but the controversy over Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing—and his resilience in responding to bad-faith attempts to misrepresent and censor his work—would define his place in art history as a radical social visionary and reluctant public policy critic.

To understand Wojnarowicz and his perspective is to understand him as an organic product of the urban cultural environment. His long relationship with New York is well documented by Cynthia Carr, a contemporary and friend of Wojnarowicz who eventually wrote his biography, Fire in the Belly. He grew up in Hell’s Kitchen, mostly left to his own devices during his teenage years, and like many itinerant young people, he discovered sex work as one of the quickest ways to make a decent wage. This would prime Wojnarowicz to discover his own queer sexuality as well as his place in the larger social power structures of the city. Fearing rejection, he was careful to keep his sex work and emerging gay identity secret from his family, which required sleeping elsewhere frequently. Because of this, he experienced significant periods of homelessness as a highschooler, barely graduating from the now-defunct High School of Music & Art on the City College campus in Harlem.

But it was through day jobs—not prestigious university degree programs, fellowships, or residencies—that Wojnarowicz built his social network of working-class artists who would become his friends, roommates, and co-conspirators. He relied on self-training and the feedback of his peers to develop his artistic voice—taking full advantage of New York’s booming informal cultural ecosystem in the 1970s and 1980s. Wojnarowicz’s network would expand exponentially through free workshops at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, chance encounters with beat poets at a laundromat on Atlantic Avenue, spray painting in abandoned warehouses on the Hudson River piers, drinking at legendary gay bars like Julius’ in the West Village, and countless day jobs at bookstores, furniture outlets, and nightclubs.

_________

Helms and Dannemeyer began their mission to smear the NEA earlier in 1989 by fabricating two controversies surrounding grants the agency made to support the work of artists Robert Mapplethrope and Andres Serrano. Mapplethorpe offended the larger conservative movement by depicting nudity, homoeroticism, and sadomasochism in his photography, while Serrano had upset the Christian Right with a photograph of a crucifix submerged in a plexiglass container of his own urine. Helms and Dannemeyer whipped up outrage in Congress and crafted a public scandal, managing to pass an amendment to an appropriations bill that prohibited using federal funds to promote, disseminate or produce “anything the NEA thought obscene, ‘including but not limited to depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts which do not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.’”

This so-called “decency clause” forced the NEA to threaten revoking the $10,000 grant that Artists Space had received to support Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing. This put the small nonprofit gallery in a terrible position: Wyatt knew that Wojnarowicz’s explicit essay would violate the clause and endanger their grant. On one hand it would be a betrayal to ask an artist to censor themselves for a funder but, on the other hand, disrupting Artists Space’s relationship with the NEA could cause a ripple effect in which private funders deem the organization too politically risky to support. Beyond this, publicly violating the decency clause could inspire additional attacks on the NEA and jeopardize public arts funding nationwide. But this predicament was Helms and Dannemeyer’s intended outcome.Carr explains it well, writing, “the far right saw a uniquely exploitable word: skilled professionals making highly charged imagery they could take out of context. The right wing frothers soon learned that, yes, nuance could be crushed, intimidation would work, and facts did not matter. Right wing media would get the lies out unchallenged.”

Wyatt and the Artists Space board encouraged Wojnarowicz to remove the names of Helms, Dannemeyer, and O’Connor from his essay, which he refused. The board then proposed a liability waiver to insulate Artists Space from the consequences of Wojnarowicz’s words, which he signed after consulting the Center for Constitutional Rights, a nonprofit that agreed to defend him pro bono should any of the named individuals take legal action. As the exhibition opening drew closer, the chairman of the NEA even asked Artists Space to voluntarily relinquish the grant, but Wyatt and the board refused. Not much later, the NEA announced the cancellation of the grant, asserting that “in reviewing the material now to be exhibited that a large portion of the content is political rather than artistic in nature.”

When Cardinal O’Connor learned of his involvement in the controversy, he released a statement condemning the NEA’s cancellation and defending freedom of expression. In response, Wojnarowicz said, “I find his benevolence questionable, if he would completely reverse the church’s repression of safer-sex information and back off from abortion clinics, I would extend my appreciation to this man. But I think it’s a political tactic and I won’t be fooled.” Wojnarowicz also had the chance to directly address the NEA Chairman at Artists Space ahead of the exhibition opening. Characteristically fearless, Wojnarowicz declaimed, “[w]hat is going on here is not just an issue that concerns the ‘art world’; it is not just about a bunch of words or images in the ‘art world’ context—it is about the legalized and systematic murder of homosexuals and their legislated silence.”

Ultimately, the NEA Chairman reinstated the grant, with the stipulation that NEA funds could not be used for the catalogue—and Artists Space agreed. Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing opened on November 16th, 1989 to an estimated crowd of 1,500 swarming the diminutive gallery. Wojnarowicz took little time to celebrate, immediately expressing his disappointment to the Artists Space board over its agreement to exclude the catalogue costs from the grant. Unfortunately, this would not be the last time public funding of Wojnarowicz’s work would come under attack. Less than a year later he would be targeted by the Christian extremist American Family Association, spurring a now-famous legal battle under the New York Artists Authorship Rights Act that would mercifully end in Wojnarowicz’s favor.

Wojnarowicz’s uncompromising defense of freedom of expression, refusal to comply in advance with censorship, and critique of unjust policy provide a playbook of resilience for the cultural sector and beyond. In the same essay, he is quick to indict the art world itself, writing that the behavior of the federal government “only follow[s] standards that have been formed and implemented by the ‘arts’ community itself. The major museums in New York, not to mention museums around the country, are just as guilty of this kind of selective cultural support and denial.” This assertion would prove to be prophetic—even after his death in 1992 Wojnarowicz’s work would continue to disturb viewers, as evidenced by the Smithsonian’s decision to censor his short film A Fire in My Belly in 2010.

Unlike the navel-gazing stereotypes often cast upon artists, Wojnarowicz was always looking outward and drawing connections between parallel struggles for justice. He implored his audience to understand that the same prejudice targeting his art was letting thousands die from AIDS and restricting access to safe abortion—it was all interwoven, all springing from the same source. As current federal policy attempts to capriciously cancel grants and dismantle public social institutions across all fields of knowledge, including the NEA, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Wojnarowicz’s irrepressible disposition and fixation on the networked nature of power is instructive.

Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell also depicts a sobering scene at Wojnarowicz’s own kitchen table, between himself and a friend who is also coping with the existential crisis of an advanced AIDS diagnosis. Wojnarowicz asks his friend:

“If tomorrow you could take a pill that would let you die quickly and quietly, would you do it?”

His friend replies, “No, not yet,” to which Wojnarowicz agrees and responds,

“There’s too much work to do.”

Rocco Praderio (he/him) is an arts administrator based in Brooklyn. He has worked at a variety of arts and cultural organizations in New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts supporting artists across disciplines. He holds a BA in Theatre Studies and Creative Writing from Ithaca College and is pursuing an MS in Urban Policy at CUNY Hunter College.