By Marley Kinser

In the evening of January 7th, fires erupted in the undeveloped mountains that cradled the town of Altadena and swept down, to the south and west. Over the next few days, firefighters fought that blaze along with one on the other side of Los Angeles County in the Pacific Palisades. Ultimately, the town of Altadena would be razed.

Whenever I would visit Altadena, where my mother lives, the spectre of natural disaster lurked in the back of my mind. It’s a town pressed up against the Los Angeles National Forest, the wildland-urban interface as amenity for the bohemians and cowboys that populate the town. We’d wind through mountain roads running errands and I couldn’t help but imagine how easy it would be to be trapped by fire or leveled in a mudslide. The City Skylines approach to a place like this, pure urbanist rationality, is to not rebuild, or at the very least, to cluster civilization in a hyper-densified core of the burned-out bit. What is the justification for putting the same structures up in the same places, and hoping that a warming planet, with more extreme weather, does not ignite here again?

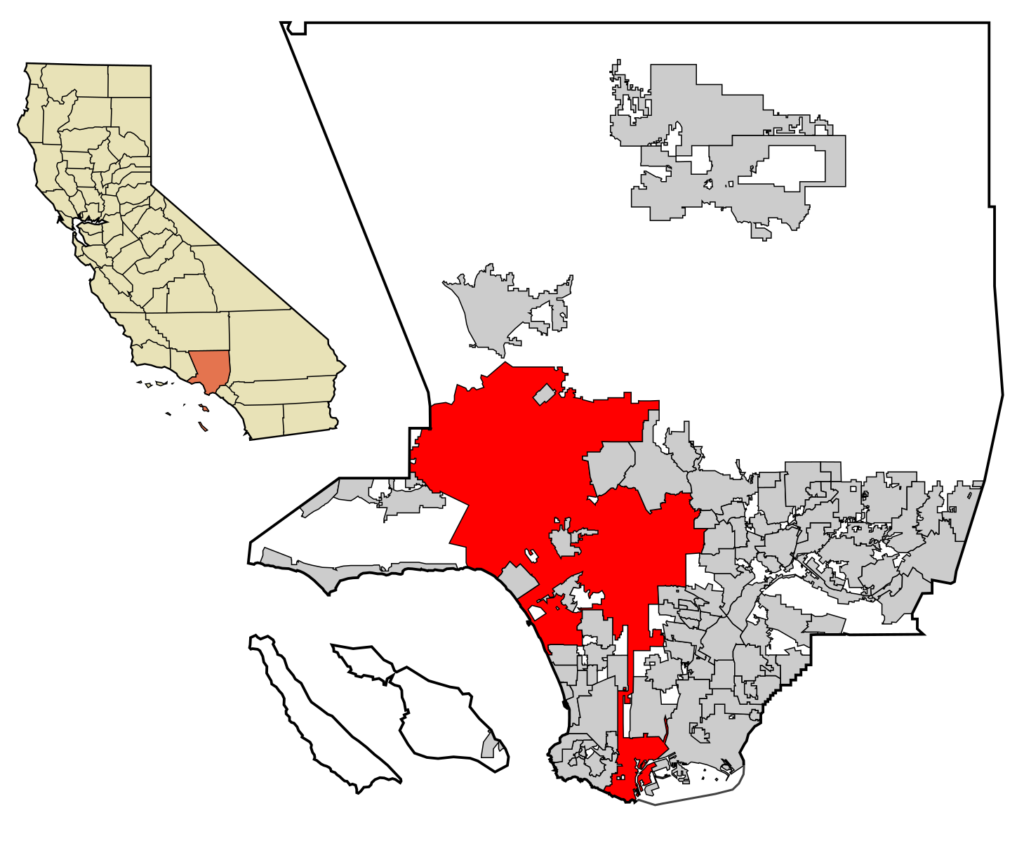

To begin to talk about the future of Altadena requires an explanation of Los Angeles County. The County, where Altadena is located, is home to nearly ten million people, largely living in communities that range from ten to twenty thousand. Some of these communities are incorporated as their own cities, with their own city councils and mayors and rules around land use, some are folded into the City of Los Angeles, and some are unincorporated areas governed by the county. There are eighty-eight cities within Los Angeles County, and over a hundred unincorporated areas; the incorporated cities range in size from the City of Los Angeles–the second-largest city in the United States, home to nearly four million people–to places like Vernon and Industry, areas exclusively zoned for manufacturing with populations in the low two hundreds (Vernon is the second-to-least populous city in the state of California, beaten only by Amador City, a gold rush town in the Sierra Nevadas that occupies 0.3 square miles).

The legal boundaries of the City of Los Angeles contain most of the valley in the Northwest, the downtown core, and very little of the east or south, save for a strip to connect to the Port of Long Beach. From this, there are also chunks randomly missing, Beverly Hills and some similar communities forming literal enclaves. It’s a shape so absurd it’s hard to come up with abstractions so clean as Italy’s boot, or even the salamander that would inspire the term “gerrymandering.” If it were a Rorschach test, it’s hard to imagine what a popular, prosocial answer could possibly be. The specific contours are less important than knowing: 1) strong municipal governance in general is hobbled by this and 2) Altadena is unincorporated and therefore has no mayor, no city council, and no police, receiving its services directly from the county.

Because of the bizarre absentee governance, what does responsiveness look like? Who makes the rules? What government actors are working on this and do people know that? There is an Altadena Town Council, but they have little power. All they do is make recommendations to the county supervisor (worth mentioning that this relationship seems quite positive and free of the jurisdictional fights that are more familiar here). The county supervisor basically functions as the mayor, and while they have a large team of support staff, Altadena’s county supervisor is also responsible for sixty-three other unincorporated communities.

Rebuilding is a given–the land beneath the char is simply too valuable. But it remains to be seen if that rebuilding will be done by a conscientious old guard that wants to shepherd Altadena, or done by industry looking to extract. It also remains to be seen in what ways the potential for further fire damage will be regulated, what role will be played by building code, legislation, and the market vis-a-vis insurance rates. What might urban planning look like, essentially building from scratch a town that until very recently existed, with a strong history and a deeply invested community?

The answer could come down to the residents. For many, they were actively drawn to the area for its diversity and affordability. Its relative lack of oversight has historically been a large part of why Altadena has thrived–it was a home for middle class Black Californians through the mid-twentieth century when the neighboring city of Pasadena passed racist segregationist laws. It also has become home to a thriving artist community, similarly enjoying being unencumbered by rules-y municipal government.

I spoke with one Altadena resident, an artist named Molly Tierney. She had claimed squatter’s rights fifteen years ago and successfully adverse-possessed the home which she lost in the fire. While she had rebuilt the house, a gorgeous 1930s mission style home, from dilapidated, abandoned ruin over many years, I was surprised to hear her say she was ultimately more attached to the land. She described “it’s still really green, my old oak trees are fine, and I have my plants that I planted fifteen years ago.”

The property had been lush, the large yard filled with agave and jade plants grown to resemble small trees. I asked if she felt she had any unique insight into the building process, having rehabbed her house so thoroughly before. Ultimately, she said, she knew how to find things cheaply, affordably, relying on reuse and more circular methods. She didn’t need or expect much guidance from the powers-that-be moving forward, she assumed that she’d be turning once again to YouTube for instruction.

Tierney emphasized, too, that her ideal vision for what gets rebuilt would not necessarily be a single-family home on the lot. Prior to squatting her house, she had lived in John Joyce University (JJU), a communal living compound for artists in a former mansion-turned-orphanage. She pointed to this arrangement, as well as to the nearby Zorthian Ranch (a former summer camp and ranch which now houses scores of artists), as examples of what could be. The ranch she described as “a weird Oasis where it wasn’t even properly permitted” with little bungalows tucked around the property for everyone, deeply affordable. She also mentioned that her current rental, about 300 square feet, had also prompted her to rethink how much space was really needed. She didn’t want to see developers come in and exploit the character of the town, but she also argued that people opposed to the kind of density present at JJU or the ranch didn’t comprehend the climate crisis.

I tried to probe Tierney on the matter of governance: who was she hearing from? Was there guidance, what kind of response would be ideal? She pointed to building codes (more sprinklers) and more resilient infrastructure for utilities (moving wires that can spark underground) for future fires, but at present, what she mainly expected was loans to aid in rebuilding, and what she mainly wanted was greater freedom to rebuild how she wanted, again citing the Zorthian riff on bungalow courts (themselves an invention of the nearby Pasadena).

She had great faith in the Altadena community preserving mutual aid and fundraising, fostering a strong community spirit to resist predatory development; though she did acknowledge the difficulties of rebuilding for older residents and for families. I caught her as she was wrapping up a day of cleaning up at her property, she told me she felt a real urgency around getting it ready and cleaned up not just for herself but for her neighbors, a sort of post-apocalyptic version of keeping the lawn mowed and weed-free.

After our conversation, I spent some time poking around Altadena on Zillow. A mix of empty lots and still-standing structures were listed. The sunny real estate copy was jarring next to the photos it accompanied:

Rare Opportunity: Rebuild Your Dream Home in the Foothills of Altadena! Situated in the heart of Altadena’s coveted foothill community, this prime lot offers a blank canvas in one of the most sought-after neighborhoods in Los Angeles County. While the original structure was lost in the January 2025 California fires, the spirit of possibility remains strong—this is your chance to create a custom retreat tailored to your vision. Located on a quiet, tree-lined street surrounded by mountain views, mature oaks, and historic character homes, this property sits on a generous parcel with utilities in place and driveway access intact. Whether you’re an end-user looking to build your forever home or a developer seeking a high-potential investment, this parcel combines location, infrastructure, and community charm. Just minutes from Eaton Canyon hiking trails, the Altadena Country Club, and eclectic shops and cafés along Lake Avenue, this lot offers both tranquility and convenience!

Neither the aforementioned Altadena Country Club nor hardly any of the eclectic shops and cafes along Lake Avenue still exist. What could make this place a sought-after neighborhood still? It’s challenging to look at the detritus of a family’s life so thoroughly upset next to the phrase “high-potential investment” and feel anything other than a blistering, impotent rage, wondering how and why we’ve organized a society that allows for such rapacity.

Over the phone, Tierney emphasized that she understood people selling their lots and leaving, especially those without insurance, or older residents that may not want to deal with rebuilding. What’s alarming is less the sellers than then the buyers: a recent report from Strategic Actions for a Just Economy found that of the ninety-four parcels sold from February 11th to April 30th, 2025, forty-five of those sales were to corporate landlords, versus five out of ninety-five sales in the same time period in 2024.

Tierney had more optimistic things to point to: her own experience with the artist’s mutual aid network, providing not just food and clothes and shelter, but also help with life administration and people to grieve with. She also pointed to the group My Tribe Rise, which was doing similar outreach with the Black community in West Altadena. In my own digging, I found articles on budding community land trusts, and groups of neighbors planning more communal and more resilient modernist typologies for collective houses.

Ultimately though, I am a bit of a pessimist, and I’m skeptical that the DIY ethos will be able to fend off predatory capital to the degree that it needs to. Then again, it doesn’t seem like there’s a municipal government in this nation that’s been able to effectively stay affordable for long-term residents in the face of seemingly sudden discovery and desirability, so it seems unlikely that incorporation or anything less DIY/more official would be of use. I don’t know what the solution is, but I hold a gentle awe for the residents that stay and insist on defending a community, a neighborhood, even in the face of its utter obliteration. One looks at the rubble and realizes that the only possible thing left to stay put for are the neighbors themselves.

Marley Kinser is a recent graduate of the Master of Urban Planning (MUP) program at Hunter College, currently working in zoning and land use for the City of New York.