PHOEBE ALLEN, JENNIFER HENDRICKS, and JESSICA KANE

On the same sunny day in early spring, two mayoral candidates visited the idyllic Open Street on Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Candidates have taken up the mantle of pedestrian streets as a sign of what is possible in a post-pandemic New York and a harbinger of democratizing changes to come. But Open Streets do not exemplify what New York could be; instead, they reveal what New York already is. As they were initially executed in 2020, Brooklyn’s Open Streets functioned as a reflection of the glaring inequities that the City has refused to deal with in more profound structural ways. As an urban service, the Department of Transportation’s Open Streets initiative mirrors inequities in the borough and reproduces spatial exclusions.

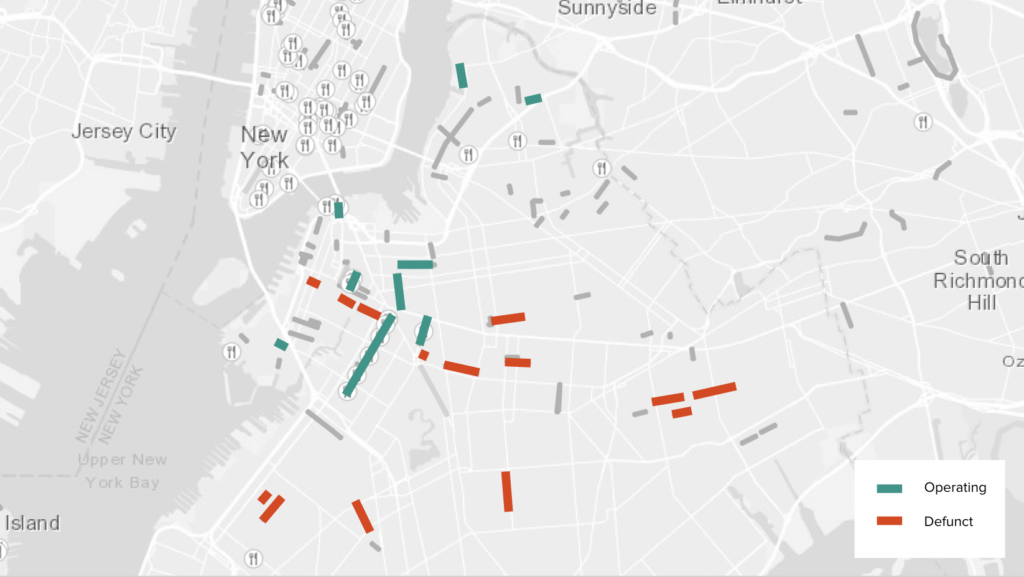

In a qualitative research endeavor taken up last semester, we visited 21 DOT-labeled Open Streets across the borough of Brooklyn to learn more about how residents experienced the pedestrian roadways. We found that the success of the program was uneven across the borough. When the Open Streets initiative began, the Mayor and the DOT were chastised for not providing more Open Streets in typically under-resourced neighborhoods, and they worked conspicuously to add more in neighborhoods hit hardest by COVID-19. But when we visited these neighborhoods, we found that many roadways designated as Open Streets were not operating as such. Instead, we found car traffic and police barricades broken on the side of the street. In contrast, the Open Streets on Fifth Avenue in Park Slope and Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights — white, wealthy neighborhoods which do not lack resources or outdoor space — were examples of the possibilities of human-centered streets.

New York City’s Open Streets project endeavored to open 100 miles of streets for its residents to use daily from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Pedestrian streets have a long history, but the transformation of roadways into pedestrian and bike-exclusive corridors gained new popularity with the introduction of the Ciclovía in Colombia in 1974. Open streets have taken on a new urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic as cities are eager to facilitate greater social distancing. With large swaths of the population spending a significant portion of the day inside their homes, cities are experiencing an acute need for the very benefits open streets can offer: active living to prevent chronic illnesses, increased social connection and reduced isolation, a positive perception of cities, and promotion of local businesses.

Where the Open Streets were functioning, they provided a vibrant sense of community for residents during this extended crisis. In neighborhoods including Greenpoint, DUMBO, Park Slope, and Prospect Heights, we found that residents were using Open Streets for a wide variety of socially distanced activities: dining out, bike-riding, walking with strollers, children playing together, dog-walking, distanced socializing, exercise classes, and more. Undoubtedly, this sort of utilization was the intention of the Open Streets initiative and illustrated a vital return of the streets to pedestrian life and local businesses.

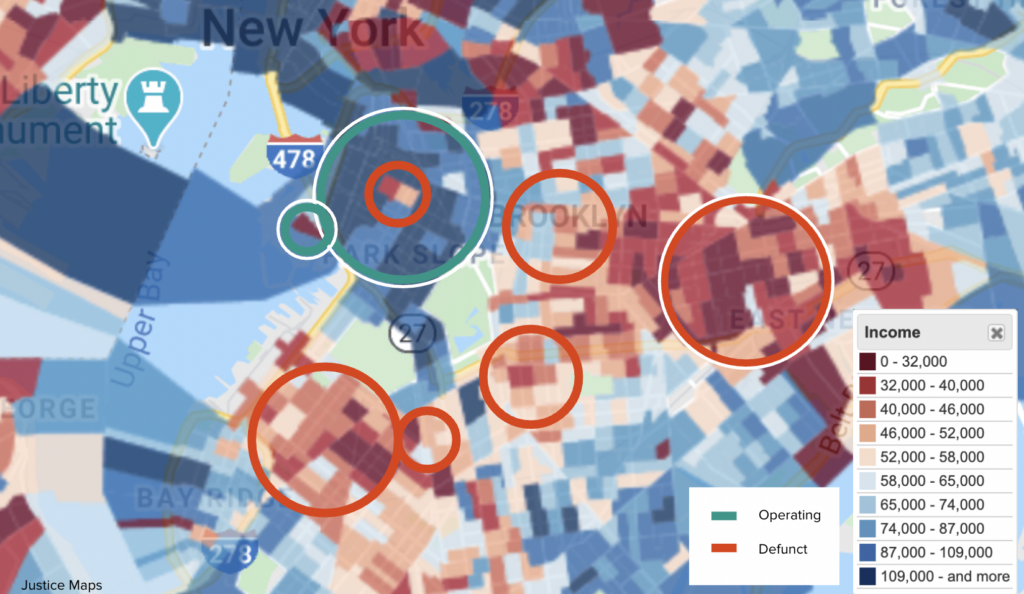

We found through our research that the geography of defunct Open Streets perpetuates the inequities already plaguing the borough: not only were fewer Open Streets designated in lower-resourced neighborhoods, but many of those designated were not operating. We completed 21 transect walks in a broad selection of neighborhoods scattered throughout Brooklyn to gain a comprehensive understanding of the state of the program in the borough. Our data analysis suggests that Open Streets in neighborhoods east of Prospect Park operated at lower rates than those west of the park. When a map of functioning Open Streets was compared with a map of neighborhood income levels, the result was stark: low-income areas had the least access to Open Streets, contrasted with higher access in middle-income and high-income areas already benefiting from existing green spaces.2 The same trend held for areas with self-reported low physical health. Despite Mayor DeBlasio’s endeavor to open 23 more Open Streets in the areas of New York City hardest hit by COVID-19, including Brownsville, East New York, and Crown Heights, those efforts fell short: every Open Street we visited in these areas was inoperative.

DOT’s rollout of the program lacked capacity-building and needed further intervention to reach the neighborhoods that needed it the most. A progress report from Transportation Alternatives four months into the Open Streets rollout determined that the program lacked momentum and cohesion to work as a serious tool to support recovery and transportation needs. The report stated that “the program remains a disconnected network of public space islands with management challenges.”3

The program’s rollout had glaring gaps in service throughout the borough, and those that succeeded often did so through the coordination of Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) and local businesses. We found lively Open Streets Restaurants along BID corridors such as Fifth Avenue and Hoyt Street. While Open Streets have provided a lifeline for restaurants during the pandemic, residents deserve access to functioning Open Streets as a public space outside the realm of private interests and property owners. It is positive that the City has found a way to aid economic recovery, but Open Streets as an initiative should also prioritize the health of marginalized and often ignored communities, regardless of commercial activity.

Alternatives exist. Stewardship programs, in contrast to BIDs, are community-led efforts that keep the operation of Open Streets in the hands of local residents. Such a setup found success in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, where a group of neighbors banded together to form the North Brooklyn Open Streets Community Coalition. The group used social media and word of mouth to gather volunteers to help maintain the street and its physical infrastructure, and to collect signatures for a petition to make their Open Street in Greenpoint permanent. An initiative like Open Streets can have the most success when it is coordinated and enforced by community members who have a personal stake in what happens on their streets. However, it is important to note that not all areas will have residents with the time or resources needed to undertake such endeavors, which could further the Open Street access divide. Other alternatives for supporting Open Streets, such as recruiting City-employed crossing guards, should be explored.

Recently the City Council passed legislation making the Open Streets program permanent. The bill also allocates funding and resources to the program and ensures that Open Streets will be distributed fairly among neighborhoods.4 If Open Streets are to become a permanent fixture of urban life as the City intends, it is all the more important for DOT to distribute the service equitably. In Brooklyn, the temporary Open Streets have amplified existing inequities in two ways — first, by their geographic distribution; second, through the ways in which they have been implemented and maintained. Given that we encountered so many examples of unmaintained Open Streets, DOT must focus its efforts on building relationships with community members, organizations, and neighborhood community centers who can then initiate and foster stewardship programs. In addition, equitable planning for Open Streets is integral to addressing the historic racial and socioeconomic inequities found in the borough. Moving forward into a post-pandemic world, city leaders must take a more holistic and social justice-centered approach to Open Streets.

Ultimately, the Open Streets initiative should reflect the needs of neighborhoods with the support of the City and community organizations. Although there are daunting faults with DOT’s Open Streets initiative as it currently stands, pedestrian streets hold promise for community resilience when implemented properly, especially in underserved neighborhoods. Last summer’s initiative should serve as a learning experience for the DOT to take equity seriously and improve the program in Brooklyn this year and in the future.

Notes

1. New York DOT, “Open Streets Overview,” https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/pedestrians/openstreets.shtml.

2. Justice Map, “Visualize race and income for your community and country,” http://www.energyjustice.net/justice/index.php?gsLayer=plural&gfLon=-73.978&gfLat=40.706&giZoom=10.

3. Transportation Alternatives, “The Unrealized Potential of New York City’s Open Streets,” September 17, 2020, https://www.transalt.org/open-streets-progress-report.

4. Christopher Robbins, “City Council Passes Bill Requiring More Open Streets In Underserved Neighborhoods,” Gothamist, April 30, 2021, https://gothamist.com/news/city-council-passes-bill-requiring-more-open-streets-underserved-neighborhoods.

Phoebe Allen is a student in Hunter’s MSUPL program and a public library worker in Brooklyn. She is interested in questions of land and ownership, public space, and community resilience.

Jennifer Hendricks is pursuing a master’s degree in Urban Policy and Leadership. She has a background in teaching and in the nonprofit sector. Her work explores sustainable urban practices and comparative urban policy. She lives in Brooklyn.

Jessica Kane is a student in the Urban Planning program born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. She is particularly interested in community planning and advocacy.