David Oke

New York is well known for its abundance of abandoned infrastructure, but it is equally storied with efforts to revitalize those artifacts of abandon. The movement for New York City to turn no longer used infrastructure into an innovative feature of city life can best be recognized through the rehabilitation of rail lines. The quintessential image of redeveloped rail lines in NYC is the West Side Elevated Line, best known today as the High Line. The early 20th-century elevated rail line, originally meant to deliver food on freight trains across Manhattan, closed down in the 1960s. After decades of survival through battles for demolition, it finally reopened in the 21st century as the High Line, a linear park with walkways, benches, art installations, and green space. Along with much fanfare and tourism, this park spurred the redevelopment of nearby West Chelsea, spawning dozens of apartment towers next to the rail line-turned-walkway.

However, this is only one side of the High Line’s revitalization story. In truth, the High Line was a failure from the perspective of equitable development. It failed to deliver rapid transit to West Chelsea, leaving the westernmost train line to remain at 8th Avenue, ensuring residents in West Chelsea walk over a kilometer to reach the nearest subway. It failed to provide affordable housing to the neighborhood, only spurring the most luxurious, upper-class housing. Since the redevelopment, the neighborhood has only gotten wealthier, with median yearly household incomes rising from $78,136 to $91,994 from 2006-2010 to 2017-2021, according to the ACS, and mean yearly household incomes rising from $139,855 to $170,245 in that same time period. Instead of providing better transportation and encouraging equity in West Chelsea, the High Line has made the area a playground for the wealthy and killed any chances of rapid transit access on Manhattan’s Far West Side.

The Adams administration, likely taking inspiration from the High Line’s influence, has been paying close attention to redeveloping several abandoned railways around the city. In 2022, Mayor Adams announced a $35 million investment for the first phase of a park-greenway that would replace an abandoned rail line in Queens. Running the vertical length of Queens from Forest Hills to the Rockaways, this right of way (the land needed to place metro rapid transit tracks down and run service) used to be the Rockaway Beach Branch of the Long Island Railroad. It operated for forty years from 1922 until its closure in 1962 due to lack of ridership and poor maintenance, eventually rendering the branch unprofitable. As it sits in disrepair, the discussion of reopening it for a different use is more topical than ever. Over in Staten Island, a similar fate of abandon befell the North Shore line of the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad (now the Staten Island Railway), which ran from St. George to Arlington on, as the name implies, the north shore of the island. Seventy years after the line’s closure in 1953, the Adams administration announced in October 2023 a plan to build forty more miles of greenway for cycling and recreation in New York City, and one of the sites chosen was this abandoned railway. With so much city government enthusiasm in returning use to these old railways, with the possibility of drastic changes in the neighborhoods they occupy, what seems to be the problem? Who could say no to revitalizing Queens and Staten Island?

Similarly to the High Line’s case, the Adams administration makes no plans for rail transit or anything besides a park or cycling track along these rights of way. The problems with revitalizing old rail lines without considering serious transportation and housing needs only worsen with New York’s outer boroughs, which are much less wealthy and well-connected than Manhattan. West Chelsea, a rich, metropolitan, and firmly downtown region in New York, may afford a missed opportunity for better transportation and housing. However, many communities in New York’s outer boroughs cannot afford such a mistake. It would be a great disservice to working-class residents who desperately rely on slow transportation to neglect returning the Rockaway Beach and SI North Shore branches to public use. For those who struggle to make rent in increasingly unaffordable housing, it would be an insult to their dignity to assume that all they need in a rare redevelopment scenario is a shiny cycling track or walkway.

There is no opportunity to reimagine transportation quite like those provided by abandoned rail lines, as the city already has the right of way, and these lines are often already nearly built out to specification for a rail connection. Little needs to be done for the Rockaway Beach Branch to make it a regular subway line, unlike the multi-billion dollar tunnel-boring engineering feat that is the Second Avenue Subway. It is easier to build rapid transit on these lines than in any other place, so let’s not waste the opportunity by stopping at recreation. It is time to bring rails, trails, and affordable housing to the communities that need it the most, with existing infrastructure.

Queens’ Rockaway Beach Branch remains the most topical rail redevelopment battleground in the city, receiving a lot of support and documentation from activists and organizers who want to see equity finally enter the topic of rehabilitation despite a lack of recognition from the city. Therefore, the primary example focus will be on Queens and the Rockaway Beach Branch. The movement to build a transit line and a greenway out of the Rockaway Beach Branch has been spearheaded by the grassroots organization QueensLink, which has urged the MTA to perform an environmental impact study on a rails and trails plan for the abandoned line. QueensLink proposes the reactivation of the LIRR branch and having the subway run from 63rd Drive – Rego Park on the Queens Boulevard Line down the right of way, making stops at four brand new stations: Metropolitan Avenue – Parkside, Jamaica Avenue (transfer to the J train), Atlantic Avenue – Woodhaven, and Liberty Avenue – Rockaway Blvd (transfer to the A train), before merging onto the A line headed to the Rockaways. Along this right of way would also be over thirty-three acres of proposed linear parks and several new cycling paths.

This rail and trail combination has been successful in many other places in the world, including the Rambla de Sants in Barcelona, Spain, which covered a raucous rail line with a linear park, serving as a noise suppressor and a connector in the neighborhood, which used to be severed by the line. Parts of South Boston’s T Orange and Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor line were tethered to the rest of the local area with a linear park rather than torn apart by a proposed highway that would have run through where the park is now. The Ohlone Greenway in Oakland, California, was built at the same time as the guideway for the BART line running over it, and it runs along the former Santa Fe railroad right of way.

A June 2021 analysis commissioned independently by Transportation Economics & Management Systems for QueensLink reports that the project would cost around $3.5 billion but would employ an extra 100,000-150,000 people, bring in $9-$13 billion in increased income, and potentially increase property development value by $50-75 billion. This unprecedented scale of value in this new corridor can finally be used for equitable, affordable housing. Luxury apartments need not dominate a post-QueensLink Rockaway Beach Branch transit corridor if City Hall decides to enforce equitable housing rules into new developments, such as extensive rent subsidies and controls, required affordable housing percentage increases for each new building, and upper price limit reductions for what is considered an “affordable” rent. Increased density of these developments can also create larger, more active communities, and can naturally decrease housing prices with increased supply. These new, dense communities along the new rail corridor will also ensure that the ridership of a reinvigorated Rockaway Beach Branch will be higher, justifying its expense. All of this considered, under $4 billion for a transit line-park combination that can serve a completely new variety of riders and spur a never-before-seen affordable housing renaissance with a three-and-a-half mile-long subway is a bargain compared to the over $4 billion cost for just the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway, a mile and a half-long line, which barely did anything to change the Upper East Side.

Despite the work done by QueensLink in gathering awareness and knowledge around this rails/trails project, the MTA has continued to ignore the project, undermine the need for it, and underestimate its cost-effectiveness. In its recent 20-Year Needs Assessment, the MTA acknowledged that the region served by a potentially reactivated Rockaway Beach Branch is primarily an equity area. Despite this, the MTA still priced the potential project as having one of the highest costs in the subway expansion assessment (not including commuter rail). There has yet to be an environmental study on a potential QueensLink project, and the Adams administration has not budged on adding rail transit to its $35 million Rockaway Beach Branch linear park investment. As such, the city, on all fronts, is shying away from expanding public transportation via this seemingly low-hanging fruit. High costs are frequent excuses made primarily by the MTA, as it has projected an estimated construction cost of nearly $6 billion, a full 70% higher than the cost from the TEMS report.

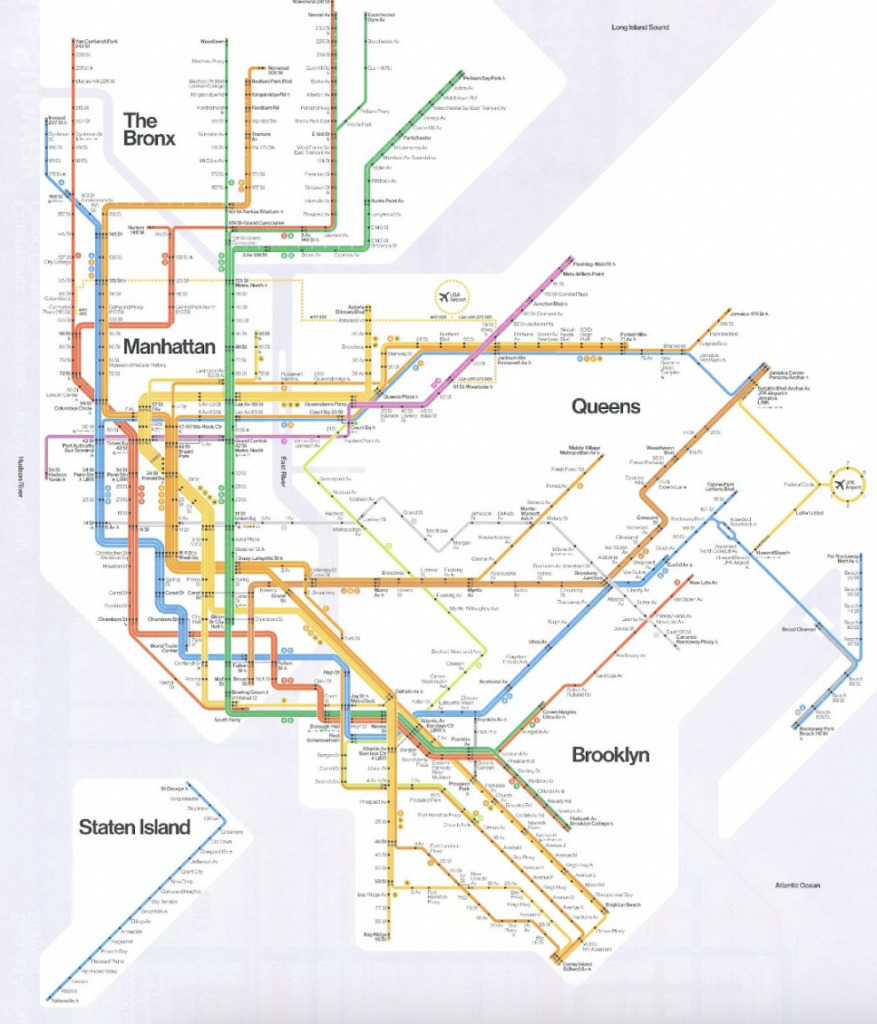

These authorities’ neglect of QueensLink is only soured by the fact that this corridor is possibly one of the most direly needed in the entire city. The Q52/Q53 Select Bus Services, which run parallel to the proposed rail route for its entire length, combined are the seventh busiest bus routes out of 78 total routes in Queens. This route connects the 7, E/F/M/R, J/Z, and A trains together. All of these trains themselves, however, run straight to Manhattan from Queens without any crosstown service. Essentially, this bus pair serves as the only cross-borough connection for riders in a sea of Manhattan-centric transportation options. If only to alleviate crowding on these buses, which also get stuck for inconceivably long periods in traffic, riders deserve a metro option for getting up and down Queens. The urgency of better crosstown connections in New York City cannot be underestimated. When looking at the picture of the entire subway, one thing becomes clear: every subway line (besides the G and shuttles) starts in the outer boroughs and heads to Manhattan. Some of these lines may even hit a third borough after Manhattan if they’re lucky!

If one wants to reform transportation in New York to accommodate the needs of working-class riders, many of whom need to go between Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, the best place to start would be to introduce cross-outer-borough lines such as the one proposed by QueensLink. These three outer boroughs of NYC, not even including Staten Island, compose 6.6 of the 8.8 million people in New York City, or 75% of the city’s population. Their needs are usually outsized by the small minority, 1.7 million, of Manhattan residents, who are often more affluent, and who currently hold a monopoly on MTA capital projects, with the Second Avenue Subway, Grand Central Madison, and the Hudson Tunnel Project holding most of its attention. While many more people work in Manhattan than do live in it, the era of only commuting to work in Manhattan is over, especially as service workers, home and care workers, and teachers find themselves having to commute within Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx instead. This decentralization of transportation away from the previously dominant borough of Manhattan is the new reality for New York’s working class, and it must be accommodated if there is any hope of achieving an equitable landscape for transportation. Reactivating the Rockaway Beach Branch for rail transit is an unavoidable first step in making this landscape a reality.

For working-class communities especially, the benefits of public park space should not be forgotten. Park space is valuable for the health of a community in more ways than just physical. On top of bringing down stress and chances for mortality, parkland can also reduce neighborhood temperatures, acting as a natural heat absorber, which is an invaluable asset during increasingly hot summers. Despite this, inequity in park access remains high, with predominantly Black neighborhoods having an average park size of 7.9 acres, compared with the average park size of 29.9 acres in predominantly white neighborhoods. Poor neighborhoods have an average park size of 6.4 acres, while affluent neighborhoods have an average park size of fourteen acres. Building parks must be considered as important, but only as part of an integrated whole of a sustainable community, along with fast, reliable transportation and affordable housing, when deciding what lower-income residents need in redeveloping abandoned rail lines.

The often ignored Staten Island also has a place in this push for taking advantage of abandoned rail opportunities. The North Shore railroad stands a significant chance at returning rail service to a community infamous for having treacherous commutes anywhere. Stripping them of a chance to cut half an hour or more off their commutes to Manhattan and elsewhere is abhorrent and not helped in any way with promises of bicycle connections via greenway. The unfortunate truth is that cycling as the only option for transportation just isn’t enough. It lacks the speed and capacity of metro rapid transit, and it is, quite frankly, still only a viable mechanism for transportation (in New York specifically) for the wealthy and already well-connected class. Instead of waiting decades for the city to come around on bike infrastructure and equity, there is a very real, immediate possible gain in transportation access for the far-flung borough if the greenway plan were to include provisions for building rail transit in the place where the rail already exists.

Redeveloped space everywhere in New York City, from the rail yard turned business park at Hudson Yards to the industrial zone turned luxury condo playground in the South Bronx to the abandoned rail line turned linear park known as the High Line, is favoring the moneyed classes at the exclusion of working-class New Yorkers who depend on increasingly unreliable transit and increasingly skyrocketing rents. An opportunity is presenting itself to easily redevelop abandoned rail spaces in the city into reliable public transportation that people of all backgrounds can access equally, surrounded by desperately needed housing, and yes, even parks. The city can no longer pretend that parks are the only option. We need much more than that to live day to day. It’s time to create spaces that work for ordinary people, not just wealthy leisurers and corporate office holders, with the most accessible, and obvious solution available. Mayor Adams, don’t let transit die for the greenway.

Hey everyone! My name is David Oke! I’m a freshman at the Macaulay Honors College here at Hunter, majoring in Urban Studies and Computer Science! Right now, my main focuses in urban planning are in transportation, spatial analysis, and climate change. I enjoy using my skills in programming to highlight issues such as urban density and land surface temperature. I just completed a semester-long fellowship at the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities, working with the NYC Climate Justice Hub and NASA to uncover the causes of and injustices surrounding climate change in urban areas, and I’m excited to continue applying my interest and love for cities, as well as my coding skills, to the issues that affect urban areas the most! This semester’s issue is my first foray into being officially published in journalism, but I’ve been running a personal blog since the start of the summer as well! My other interests include cycling, lifting, and cinematography!

Check out my blog: https://urbanblogs.netlify.app/