FERNANDO TIRADO

The COVID-19 pandemic is unique among most disasters over the last 20 years because of its greater impact on human life than on the built environment. Unlike past storm-related disasters, which are often quantified in their financial costs to infrastructure and housing, the costs of the pandemic go beyond any monetary amount due to the profound psychological and societal impacts that are not easily measured. While the current response to the pandemic is on increasing access to vaccinations, investing only in recovery efforts creates “disconnect between the policies intended to protect public health from disasters and the resulting adverse effect on those whose health is most at risk.” Combined with other factors, these compounded, neighborhood-level traumas can foster Adverse Community Environments (ACE) that contribute to further erosion of social cohesion and greater incidence of poor physical, behavioral, and social well-being in the affected neighborhoods over time. Communities most impacted by COVID-19 not only need assistance in recovery, but additional support to thrive in the face of future adversities. For this reason, community resilience needs to be elevated as a public health priority. Where, then, is the political will to support recovery efforts and prevention strategies at the local level, with a focus primarily on people who are the most vulnerable to disasters?

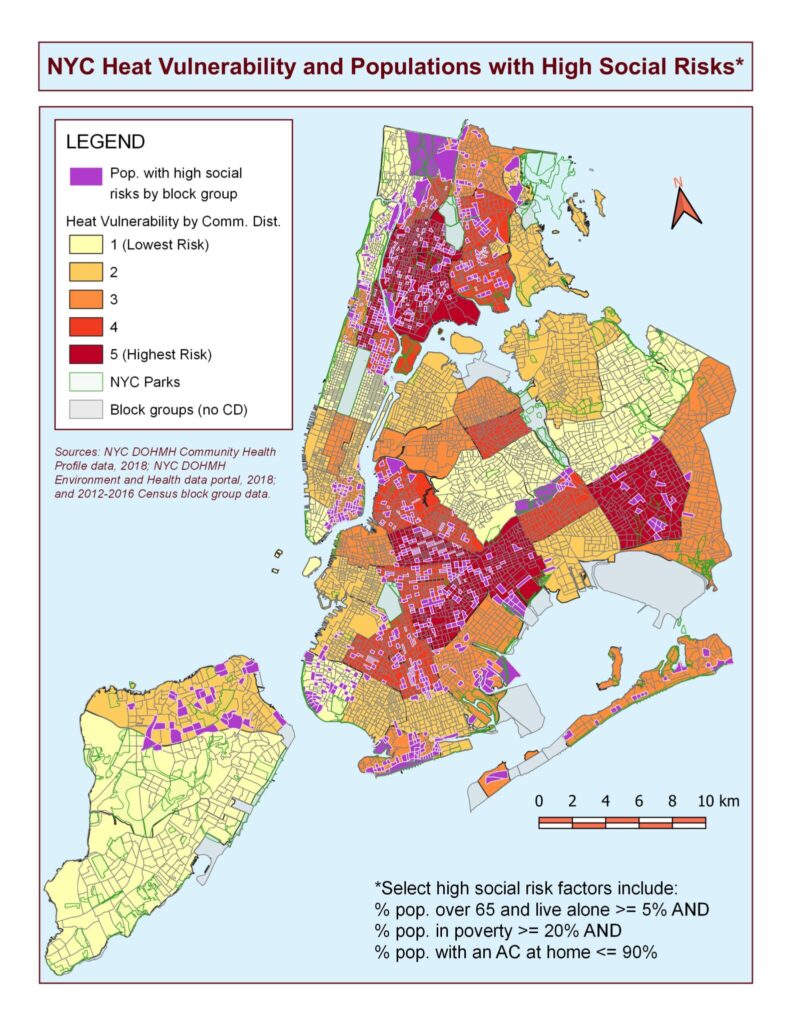

The impact of the pandemic has hit the Bronx particularly hard, as it is the county with the highest rate of death from COVID-19 in New York State, according to the NYC Health Department. Pre-existing health conditions such as obesity played a significant role in who was most susceptible to infection to COVID-19. However, other socioeconomic factors have an impact as well, and it is well documented that the social determinants of health are weighted as having the greatest impact on overall health. These determinants are considered upstream from disease burdens, according to organizations such as BARHII, and are greatly influenced by social structures and historic policies (e.g. the role of racism and childhood poverty on overall health). It should be no surprise, then, that marginalized individuals and communities with historically poor health outcomes across the country were the hardest hit by COVID-19, and these groups will remain the most vulnerable to all future disasters and emergencies as long as the status quo is maintained.

Before the pandemic, the US was experiencing an obesity epidemic. Obesity rates rose sharply over the last decade, with 40 percent of the population over 20-years-old considered obese according to the US News & World Report. According to the CDC, overweight or obese people account for approximately 78 percent of those who have been hospitalized, needed a ventilator, or died from COVID-19. The obesity epidemic is driven primarily by widespread food insecurity and a food system spurred by global markets that exploit hunger in local and primarily poor communities. COVID-19 has turned out to be more than just a contagious disease; it has also exposed the ugly and uncomfortable truths about how people’s everyday health is impacted when disasters occur.

There can be a space for urban policymakers and advocates to improve and strengthen these systems and increase social capital on the community level by focusing on developing general community capacity to take collective actions that ensure social and health equity for all residents. A report by the US Department of Health & Human Services recommends that local governments first improve and strengthen everyday systems and social connections to build up the resiliency of individuals and communities before, during, and after disasters.

New York City stands out against the rest of the country in that it has, in many ways, invested in strategies to reduce racial disparities and health inequities, with city agencies coordinating with each other on specific issues such as food insecurity, mental health, and heat mitigation. An example of this level of coordination can be found in the Hunts Point Forward plan, spearheaded by the NYC Economic Development Corporation, which works with city agencies to design comprehensive strategies to reinvest in Hunts Point by addressing physical, behavioral, and social resiliency issues. Additionally, the Board of Health recently passed a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis and requesting that the Health Department expand its anti-racist work.

A first step to expanding efforts to reduce health inequities and build community resiliency should be investing in building general community capacity, as well as treating racism as the result of a slow-moving, man-made disaster that has disproportionately impacted poor, urban, and segregated populations. With regards to addressing the syndemic of COVID-19, obesity, and food insecurity, city agencies must make themselves available to co-develop recovery plans with residents at the table, and invest in goals that prioritize their voices overbroad, glossy, and convenient strategies. We will not prevent another pandemic from occurring, but we can mitigate its effects by working to understand the links between poverty and food consumption, and supporting economic and social infrastructure that provides better access to healthier foods.

We can invest in preparing residents to become more resilient in the face of future disasters by understanding and investing in their physical, social, and emotional well-being beyond the city’s other emergency response priorities. As public health scholar Maureen Lichtveld explains, “We fail to invest where the benefits are most sustainable.” This can result in a failure to develop prevention measures while instead continuing to disproportionately spend limited resources on short-lived response activities that do not effectively help communities recover from the present crisis, or prevent and prepare them to deal with the shocks and stressors of future emergencies.

New York City has also made efforts to begin to build community resilience, though additional multi-sectoral initiatives are necessary. Currently, New York City supports community resilience through initiatives like ThriveNYC–which includes services such as NYCWell, a 24/7 support line to help people experiencing a mental health crisis. Although this is a good first step, this model requires those in need of assistance to be knowledgeable consumers of municipal services, something most people are not. Instead, cities should do more to make resilience-building efforts easily accessible on the local level. Moreover, there is no single domain or sector that can build community resiliency. Fostering resiliency requires multi-sectoral collaboration on a hyperlocal level to identify and develop solutions that improve general community capacity with their local economies, disaster communications, and increased social connectivity.

One recommendation that can cut across multiple levels of resilience is universal broadband, which can support physical and mental telehealth, access to critical social services, and help people stay connected throughout a disaster. Just before the pandemic, less than 1 in 5 residents in many community districts did not have broadband access. During the height of the pandemic, households without internet access faced barriers to accessing remote education, appointments for COVID testing or a vaccine, and information on the nearest food access locations. Medical providers struggled to stay in touch with patients, and mental health advocates scrambled to make tele-mental health billable for their medicaid patients. If universal broadband had been in place, these barriers to accessing critical resources could have been mitigated. Through resilience-building efforts such as universal broadband, communities can be better situated to address future daily and traumatic wellbeing challenges.

The slow-moving disasters of racism, poverty, obesity, and food insecurity collided with the outbreak of COVID-19 in March 2020, creating a perfect storm that led to the disproportionate negative impacts on poor communities of color in NYC, particularly in the Bronx. Many people have focused their energy on what could have been done to prevent COVID-19 in the first place, but this falsely assumes that we can prevent health or natural disasters from ever occurring. We cannot. However, as policymakers and advocates, we can work with communities and stakeholders to foster resiliency and minimize the impact of future disasters while leading the way in designing a just recovery.

Fernando P. Tirado is pursuing a master’s degree in Urban Policy and Leadership at Hunter College. He currently works with the NYC Dept. of Health & Mental Hygiene as an analyst and serves as the Director of New Initiatives for the Bureau of Bronx Neighborhood Health. His focus is on developing neighborhood health planning initiatives and community resilience to improve health outcomes.