TREVOR LOVITZ

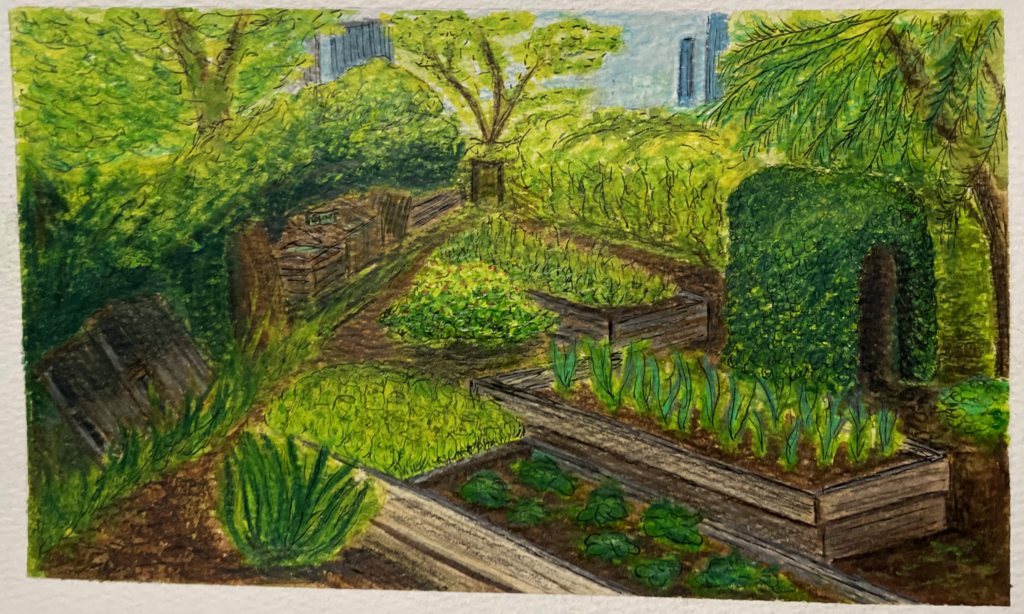

On a brisk November afternoon, the urban farmers of Smiling Hogshead Ranch gathered to celebrate the ten-year anniversary of the ranch’s founding. Standing in a large circle and gripping mugs of mulled wine, the farmers were surrounded by the ranch’s charmingly ramshackle rows of crops, herbs, flowers, and compost. The scene was framed to the west by the incongruent luxury residential towers of Long Island City. Further still in the distance loomed the Manhattan skyline.

Gil Lopez, the driving force behind the ranch’s founding in 2011, addressed the circle. Reading from a copy of the text that will soon be inscribed on a land plaque on the grounds, Lopez spoke:

As land stewards, we Smiling Hogshead Ranch, an urban farm collective, acknowledge that the land which we have occupied in order to farm, compost, and commune together exists within the unceded territories of the Munsee Lenape and Canarsie tribes, who were among the first stewards of Lenapehoking – also known as New York City… We resolve to be critical of our own participation in remaining colonial structures, policies, and ideologies, and to respectfully honor and integrate native agricultural practices, traditions, and knowledge into our work at Smiling Hogshead Ranch and everywhere.

Around the assembled group, the trees and shrubs of Smiling Hogshead Ranch were dotted with hues of yellow and orange, its crops ready to give up a final bounty before the first frost would bring this year’s harvest to a close.

Enter Smiling Hogshead Ranch

Located between Long Island City’s Industrial Business Zone (IBZ) and Amtrak rail lines, Smiling Hogshead Ranch (SHHR) emerges suddenly and without enclosure—an oasis of green in a gray landscape of production and infrastructure. For the past decade, volunteers here have cultivated a wide array of crops, ranging from household staples(zebra tomatoes, peaches, radishes, pears, grapes, garlic, ginger, and watermelon) to the slightly more uncommon (paw paws and hardy kiwis). Complementing this cornucopia are raspberry and currant bushes, fig and apple trees, and a variety of herbs and flowers.

The ranch also maintains a robust composting operation. In its function as a community drop-off site for food scraps and other biodegradable waste, the ranch composts as much as 1,000 pounds a month. Annabelle Meunier, a 2014 graduate of Hunter’s urban planning program and a SHHR board member, states that the ranch uses advanced composting techniques such as windrows to process the waste and in doing so builds up the ranch’s soil and helps remediate any contaminants left by decades of industrial use. This function of the ranch assumed increased importance during the pandemic, Meunier says, when the city suspended its fledgling Curbside Composting program and New Yorkers who had bought into the program looked for other resources to process their scraps.

In addition to crops and compost, the Ranch is home to a litany of other facilities: an apiary, a sandbox for children, shelter and provisions for feral cats, and an amphitheater where cultural programming is conducted by night. Past productions include the works of Shakespeare, educational puppet shows, and a “queer eco-medy.” Core to the mission is ecological outreach and education. Buses ferry in schoolchildren from Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx on field trips to see a working urban farm. Volunteers from the ranch will lead the students on tours of the farm, lecturing on crop cultivation and compost–but Lopez admits that this can be challenging, as the volunteers, almost all of whom work during the day, often need to take time off to accommodate the schools.

With its rows of crops, its mounds of compost, and its homespun and whimsical structures bounded by tagged and crumbling concrete infrastructure, Smiling Hogshead Ranch is altogether unlike any other public space in the city. An unsuspecting visitor might be forgiven, on first visit, for daydreaming that outside society has collapsed and that here a ragtag group of survivors banded together to restart society anew—only this time reconceptualizing it along more equitable lines.

Founding the Ranch

This is not far from what happened—at least the second part. It began as an experiment in guerilla farming. In 2011, Gil Lopez, freshly transplanted from Florida to western Queens and with an insatiable urge to garden, found himself stymied by long waitlists for beds in local community gardens. He organized a group of four friends and likeminded activists and they set about scouring the vacant lots of industrial Long Island City on bike that winter, searching for a likely lot on which to begin a new, different garden.

“We settled on [what would become] Smiling Hogshead Ranch on the railroad tracks because it was big, there was no fence, no sign saying ‘posted’,” says Lopez. Owing to its location on the edge of the IBZ, foot traffic was scarce in the vicinity after normal business hours, enabling the friends to surreptitiously begin the work of starting a guerilla farm. After collecting soil samples and having them tested at the University of Massachusetts to ensure the lot could support full-scale cultivation, they set to work. Seven more volunteers soon joined and thus Smiling Hogshead Ranch was founded.

In true tactical urbanist form, Smiling Hogshead Ranch was from the start an illicit operation. To evade detection, the friends would farm by night the decommissioned section of railroad track, which is owned by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). The lot is part of what is known as the Degnon Terminal, a long-dormant network of rail which formerly transported commercial freight to and from the nearby factories of Long Island City, such as American Chicle, the manufacturer of chiclets; the Ever Ready Battery Company;and the makers of Sunshine Biscuits—now the site of LaGuardia Community College.

Before Lopez and his friends began occupying the tracks, the sole users of the space were people engaged in sex work and scattered homeless encampments. Perhaps for this reason, the MTA sanctioned the eleven ranch founders to continue operations on their lot. Since then, a lease has been arranged whereby Smiling Hogshead Ranch can work this portion of the Degnon Terminal rent-free. Three noteworthy clauses in the lease are: 1) SHHR is forbidden from erecting permanent structures, 2) SHHR assumes all liability for incidents within, and 3) SHHR’s right to continue working the space is subject to annual renewal.

In Search of the Ideal Urban Public Space

Like other community gardens in New York City, SHHR receives support in the form of technical training and supplies from GreenThumb, the division of the Parks Department that administers the city’s 500-odd community gardens. However, Smiling Hogshead Ranch deviates from the guidelines of GreenThumb in that it lacks a fence. That Smiling Hogshead Ranch is without enclosure is critical to the Ranch’s self-conceptualization as a latter-day commons. “Commons,” in urban history, functioned as space collectively owned and worked by a city’s residents, outside of direct stewardship by municipal government. Early American cities such as Boston and New Haven contained such public communal resources. However, commons have all but vanished through the process of enclosure (the physical fencing of the space as it transfers to private control).[1]

SHHR, as an unenclosed farm collective, represents a reversal of this process when theoretically situated. As a hand-painted sign at the Ranch proudly proclaims, “Reclaim the Commons. Cultivate Community.” In this lens, the production of space at SHHR dovetails with Sharon Zukin’s formulation of ideal urban public space: “public stewardship and open access.”[2] Such spaces are becoming scarce due to what Setha Low and Neil Smith call “the redaction of public space” under neoliberalism.[3] Under this regime, cities such as New York are increasingly starved of truly equitable and accessible public space as the provision of public space is increasingly outsourced to private actors, whether it be in the form of privately owned public spaces (POPS), public-private conservancies, or such products of the billionaire imagination as “Little Island.” If we subscribe to David Harvey’s interpretation of Lefebvre’s “right to the city” as the “right to change ourselves by changing the city,” then in this light SHHR stands out as a powerful affirmation of the agency of organized New Yorkers to produce alternate visions of urban public space, even under the constraints of neoliberal regimes.

While Smiling Hogshead Ranch owes its fenceless perimeters to its sitting in a lightly trafficked industrial district as much as to its political philosophy, Lopez and Meunier state that there are consequences to this decision. Volunteers at the ranch contend with crop theft, vandalism, truant students, and drug users. The volunteers of SHHR do their best to enforce acceptable use, Lopez says, without resorting to the NYPD or surveillance—the preferred recourses of more tightly controlled public spaces.

Gardens and Farms

In the winter months, the urban farmers will conduct plant planning days where the next seasons crops are chosen by consensus. Come spring, it’s all hands on deck for Planting Day when the seeds for the upcoming season are laid. Throughout, the process is cooperative, and the crop yields are shared with all. This stands in contradistinction with many community gardens, where members are assigned a bed on which to grow—the waitlists for which often run for years. Community gardens organized in this mold run the risk of reproducing patterns of exclusion and privilege, which they are designed to combat. In the same token, in September of 2021, the city announced it would convert Little Italy’s Elizabeth Street Garden into supportive housing for seniors, prompting debate. Further inquiries into the matter sparked revelations, however. The Elizabeth Street Garden had in effect functioned as a pseudo Gramercy Park— often locked and inaccessible to the public.

The pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated many pre existing inequalities, one of which being unequal access to green space, in New York City and beyond. The model of Smiling Hogshead Ranch, which by virtue of its collective format can absorb many new members, is perhaps a more equitable model in the provision of green space. The by-bed arrangement does not “cultivate a communal understanding of how we work together,” Lopez said, and gardens in this mold often struggle to keep their common areas clean. An ambitious planning proposal holds the promise of bringing increased prominence to the ranch. Perhaps, then, other community gardens will take stock of its example.

Visioning the Future

In 2015, the MTA released a request for expressions of interest (RFEI) for the adaptive reuse of the Montauk Cutoff, a 1/3-mile disused elevated railroad right-of-way that Smiling Hogshead runs alongside of and feeds into. “The purpose of this Request for Expressions of Interest (“RFEI”) is to explore the possibility of preserving the Montauk Cutoff right-of-way through leasing or otherwise conveying it to a third party for adaptive reuse if or until such time as it is once again needed for transportation use” the RFEI stated.

In pursuing the adaptive reuse of elevated rail, the MTA was quite clearly taking a page from the High Line, perhaps the most notable instance of adaptive reuse in recent history. Repurposing the ruins of the Fordist city has become a popular planning intervention in the neoliberal era. Since the debut of the High Line, other sites from New York’s industrial heyday have received a second lease on life through this paradigm; Gantry Plaza State Park on the Queens waterfront, Brooklyn’s Domino Park, and Concrete Plant Park in the Bronx. However, while the above instances were often conceived in pursuit of an economic development agenda, the proposals garnered by the MTA’s RFEI are of an altogether different model, one more closely resembling the mission and philosophy of Smiling Hogshead Ranch.

Dutch Kills Loop has emerged as the leading proposal for the adaptive reuse of the Montauk Cutoff. The loop is, according to an executive summary on its website, “a proposed 1.4 mile circuit of public walkways, bridges, and park spaces that enlivens and connects a restored Dutch Kills, an inlet of the Newtown Creek in Long Island City, Queens, New York.” The proposal coalesced from multiple ecologically-minded visions for the area surrounding Dutch Kills from community organizations and NPOs such as River Keeper, the Newtown Creek Alliance, and Smiling Hogshead Ranch. In the finalized proposal, Smiling Hogshead Ranch would serve as an integral part of the overall circuit, in addition to informing much of the loop’s overall philosophy.

Mitch Waxman, a Queens-based photographer and board member and resident historian of the Newtown Creek Alliance (NCA) summarized the philosophy of Dutch Kills Loop as follows: “The idea that we’re currently working under at NCA is that the environment is thoroughly broken and what we want to do is build the foundation for a future where the environment and industry are able to co-exist.” In its unique engagement with the industrial city, both in the adaptive reuse of its ruins but also by running alongside contemporary spaces of production, Waxman calls Smiling Hogshead Ranch “an exemplar” and a key real-life expression of the philosophy that the proposed DKL hopes to embody.

“If we look at the Montauk cutoff not as being abandoned railroad tracks, not as a site that needs fencing,” Waxman continued, “but instead as a green ribbon that goes through a particularly dark thicket, that is otherwise hyper compromised environmentally, we might be able to begin building a proper ecological foundation [for the future].” Waxman sees Smiling Hogshead participating in this vision as a “green anchor that we can have other ribbons feed back to.”

Lopez who, like most of the urban farmers, has been an outspoken proponent of the Dutch Kills Loop, sees the proposal as “an extension of the ideas central to the ranch” and hopes that the vision, if realized, would provide SHHR the additional resources it needs to expand and maintain its program of ecological outreach. All indications are that the future of the ranch is bright and green.

Organizing Western Queens

At the time of the Ranch’s founding in 2011, the erstwhile solitary obelisk of the Citigroup Building towered above the trellises of Smiling Hogshead. Since then, the skyline of western Long Island City has been utterly remade, stemming from a 2001 rezoning under the Bloomberg administration. Today, the Citigroup building is joined in its lofty ascents by an array of new high-rise luxury residential developments that have sprung up on the other side of the tracks opposite the ranch. Nearest of these are the white edifices of 5PointzLIC, one forty-seven stories high, the other forty-one. Completed in 2020, it occupies the site of the famed graffiti mecca of 5Pointz, which was abruptly whitewashed in 2013 and then controversially demolished to make way for the upmarket residences.[4]

On the other side of the ranch—and at the other end of the urban restructuring process—lies the industrial business zone (New York as union town), which continues to be chiseled away through repeated rezonings. If competing visions of the city converge at Smiling Hogshead Ranch, then the ranch and its farmers obstinately project a vision of their own. SHHR has emerged as part of a constellation of community-based organizations in Western Queens, which have increasingly banded together to contest the logic of the neoliberal development agenda that has dominated Long Island City the past two decades.

Like other community gardens, participation at Smiling Hogshead Ranch is more than crops, it is a vehicle to deeper levels of civic engagement. As Lopez put it, “When you’re in a group and you feel that support, it becomes easier to articulate what it is that is the problem with what is being proposed and it becomes easier to stand up and voice your dissent when you know you have people behind you, backing you. This is a big part of the community we’re cultivating at the ranch.”

Organized community resistance has led to multiple triumphs against neoliberal development in the highly contested space of Western Queens. The most notable instance occurred in 2019, when fraught community resistance to Amazon’s proposed “HQ2” in Long Island City led to the multinational behemoth pulling out of the deal. In yet another sign of the shifting tide against neoliberalism, one of the properties slated for the HQ2 package (the Department of Education facility at 44-36 Vernon Boulevard) is being evaluated as a site for the emergent Western Queens Community Land Trust.

Similar resistance from Smiling Hogshead Ranch and its allies led to a rebuke of the Economic Development Corporation’s master plan for Sunnyside Yards, a vast rail yard that is commonly referred to as the greatest undeveloped tract of land in New York City today. Lopez sees Smiling Hogshead Ranch as being an integral part of a web of community organizations which have collectively framed resistance to neoliberalism:

There’s a lot of organizational strength in these numbers, in these people, in these ideas, and we’ve been tested twice through Sunnyside Yards and Amazon’s HQ2 and we showed up in exactly the way we needed to in order to beat them back. Us Western Queens activists are a bunch of bad asses that ain’t backing down from big corporations, the Economic Development Corporation, or anybody else. These are our lives, this is our city, and this place is not for sale.

Smiling Hogshead Ranch Comes of Age

More than crops are grown at Smiling Hogshead Ranch. At the ten-year celebration, the urban farmers were celebrating much more than the ten harvests, tens of thousands of pounds of waste composted, or countless school tours and ecological outreach. What was being resoundingly celebrated here, above all else, was the formation of community.

The urban farmers went around in a circle, describing, in one word, what they experienced at the ranch. Words included “connected,” “enlightened,” “inspired,” and “fulfilled.” In a final speech before the cutting of the cake, Lopez addressed the circle, “let’s be leaders within Smiling Hogshead Ranch. Let’s be leaders within our community. Let’s be leaders in New York City. Let’s take the power and the recognition and everything that comes with being part of this garden and own it— and grow more.”

When asked how she thought the example of Smiling Hogshead might be reproducible throughout the city, Meunier considered the example of a new guerilla garden that came about during the pandemic. In June of 2020, a group known as the Western Queens Guerilla Gardeners broke into a vacant lot on the corner of Skillman Avenue and 45th Street in Sunnyside, Queens and began working it. The group have since established a new community compost site, winning the private landlord’s temporary assent. In this sense, the example of Smiling Hogshead Ranch is clear, Meurnier says. “It’s not the easiest thing to pull off, but if you’re motivated you can create a space for ecological purposes where you live, and that’s pretty huge.” Invoking the legacy of 596 Acres, the now-defunct organization which flagged vacant lots in New York for community stewardship, Lopez was perhaps more succinct in summarizing the lesson of Smiling Hogshead Ranch: “If you want it, take it.”

Notes

[1] Low, Setha, and Neil Smith. 2005. The Politics of Public Space. New York: Routledge.; Smith, Neil. 1984. Uneven Development Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 116.

[2] Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Culture of Cities. Cambridge: Blackwell, 35.

[3] Low and Smith, The Politics of Public Space, 1.

[4] Chaubul, Mekhala, and Taylor Tatum. 2015. “Lessons from 5Pointz: Toward Legal Protection of Collaborative, Evolving Heritage.” Future Anterior: Volume 12, Issue 1, 77-97.

Trevor is a second-year urban planning candidate. He also received his bachelor’s in geography from Hunter. His day job is as a GIS analyst.