GREGORY SUTER

With a flashing green light and familiar chime, my bike unlocks from its dock and I’m on my way. Today marks my 2131st Citi Bike ride over the past four years. My high ride count reflects the privilege of many varieties, but perhaps most consequential is geographic. Almost all my time is spent within the Citi Bike network, which now covers all of Manhattan and neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, and the part of the Bronx closest to Manhattan. To reside within the Citi Bike zone is to have near-constant access to a critical last-mile transit option at no extra charge on top of the annual membership fee. Conversely, those outside the zone in neighborhoods farther from the central business district in Manhattan already have less access to public transit are now further constrained to traditional transportation modes or a personal micro-mobility vehicle. While a bikeshare network has the potential to mitigate transit disparities, the current system in NYC further exacerbates the problem.

Citi Bike, however, is owned and operated by Lyft, is currently expanding its system to neighborhoods previously isolated from this life-changing micro-mobility solution. The Phase Three expansion started in 2018 and is expected to continue throughout 2023, bringing bikeshare deeper into Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. At this critical moment, on the eve of Citi Bike’s vast expansion, this article asks what does it mean to be included in the Citi Bike zone and what do the edges of its network look like?

CITI BIKE BEACHHEAD IN LONG ISLAND CITY EAST

Our journey starts near my apartment in Hunters Point, Queens. I quickly bike under the Pulaski Bridge and enter the manufacturing district of Long Island City (LIC) East. This strange pocket of the zone only has four Citi Bike docks on the leeward side of the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) cutout. While these docks may feel incongruent in this otherwise quiet industrial expanse, they owe their existence to a nearby Lyft office. In some instances, like here and the Sunset Park location (prior to the 2019 expansion), the tech giant will defy its usual spatial logic of expanding along clusters of office and residential corridors and instead place docks where they can be of service to their office workers. While distant, these docks still serve a role;they connect LIC East’s offices and schools to key transit hubs in downtown Long Island City or to the LIRR Hunters Point subway station. Interestingly, here on the edge of the zone I came across dozens of Revel scooters littering the curb, perhaps further indicating the last-mile transit needs of this industrial neighborhood.

Parked under the Long Island Expressway and alongside a Citi Bike dock adjacent to LaGuardia Community College, Revel scooters provide workers & students in LIC east a non-car travel alternative. Access to micro-mobility for non-car users offers a connection to established public transportation routes or a direct connection between two places outside transit networks, credit: Gregory Suter.

HARD AND SOFT EDGES

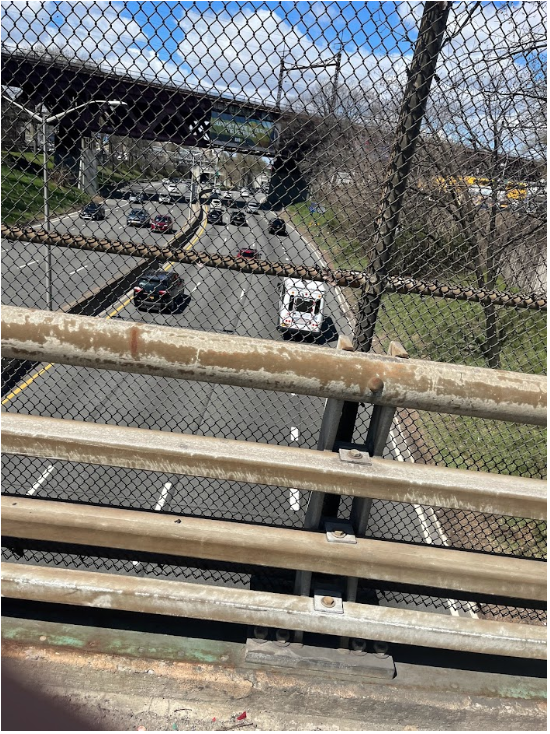

Next, I traveled back over the vast physical edge of the LIRR and Amtrak rail lines, moving northeast along Northern Boulevard to Woodside. Here, I find many of the edges Kevin Lynch describes in his “Image of the City”. The rail lines act as formidable physical edges, stifling movement across the urban space and obstructing walkers, bikers, and drivers traveling to Sunnyside and Sunnyside Gardens from LIC and Astoria. The few bridges that straddle the divide are imposing, hectic car-dominated tendrils and it is unsurprising to see few pedestrians or bikers brave the crossing.

Looking northwest across an imposing bridge it is unsurprising few bikers choose to cross over the railroad tracks, credit: Gregory Suter.

Here, the hard edge of the rail lines is mimicked by the soft edge of the Citi Bike zone; the lack of bikeshare on the southern side of the cutout means few trips will occur between these neighborhoods via bikeshare. Residents in Sunnyside currently exist outside the bikeshare system, while residents within the zone are loath to stray far from the docks into this dockless frontier, lest they incur an overage fee. These practical and financial considerations, compounded with the mobility fragmentation posed by LIC’s hard infrastructural edges and soft bikeshare borders, deeply frustrate movement through Western Queens.

PERCEIVED EDGES FORM FROM SAFETY CONCERNS

Woodside represents the easternmost edge of Queen’s Citi Bike zone, with the farthest dock located on 62nd street and Northern Boulevard. Though my intention is to stick as close to the boundary as possible, as I ride farther along Northern Boulevard, the road widens, the buildings are set farther back, and I begin to feel threatened by speeding, careening cars.

Even as a bold and comfortable biker, this landscape intimidates me. If I absolutely had to continue on this street, I likely would have transitioned to the sidewalk. Technically this is a traffic violation but I would rather get a ticket than be hit by a car on this road. Additionally, had I been riding my own bike I would have been concerned about getting a flat tire here. Just another advantage of using bikeshare, users are not responsible for maintenance or repair costs to bikes which helps eliminate financial barriers to biking, credit: Gregory Suter.

With only the symbolic paint of the bike lane for protection, I stop to consult Google Maps and realize if I continue on this street, no safe north-south routes exist in the rest of the Woodside zone. This predicament represents a common one for urban bikers. Citi Bike’s mere existence does not suffice to create a biking community. Though some people will bike in any conditions, most people will only bike where they feel safe. In an older study, the City of Portland estimated 60% of their population fell into this “Interested but concerned” camp. In order to expand the biking population in New York City and abroad, municipal planners, advocates, and politicians must break down another edge: the edge of safety and bike infrastructure. Realizing I am on the wrong side of this edge, I cautiously choose to divert my route north along 43rd street.

MIX-USE NEIGHBORHOODS OFFER A WELCOMING EDGE

In Astoria, like Woodside, real bike lane protection is scant, with only a faded band of paint to demarcate bikers’ space on the one-way lane. However, unlike the frenzied arterial of Northern Boulevard, this dense residential neighborhood features narrow streets clustered with parked cars, calming traffic and my nerves. Docks here are plentiful, scattered throughout, and often near restaurants and intersections. Thanks in large part to a healthy mix of residential and commercial uses, the docks in Astoria appear to be well-balanced, neither totally full nor devoid of bikes. The dock usage is likely healthier here because the bikeshare option is not truly on the edge, but rather ensconced within the zone, and as such attracts riders from multiple directions.

Bikeshare seamlessly fits into these streets in Astoria where docks are located near intersections with restaurants and small stores. Studies continue to show that converting car parking for bike and pedestrian spaces increases sales, credit: Gregory Suter.

BIKESHARE BREAKS DOWN HISTORICAL EDGES

At Astoria Boulevard, the bike lane dead ends into Grand Central Parkway, the unsightly and heavily-trafficked chasm cleaving Astoria from Ditmars-Steinway. Often, these highways were intentionally built through Black and Latinx neighborhoods, thus concentrating the accompanying noise and air pollution in already burdened areas. These roads also formed edges between communities, severing existing connections, and contributing to post war urban decline. Crucially, the Citi Bike zone straddles this divide, empowering the movement of bodies across a hard edge–unlike what we saw in Sunnyside and Woodside. In recent years, cities around the world have begun to tear down urban highways that previously functioned as formidable boundaries. The work to reconnect these previously severed neighborhoods remains a considerable task. Thus micro mobility transit solutions such as Citi Bike assume paramount importance in overcoming the hard edges in the urban space wrought by decades of car-centric planning, and perhaps serving as a balm to the legacy of these divisive policies in marginalized communities.

LAGUARDIA REMAINS UNFRIENDLY FOR BIKERS

As I ride through Ditmars-Steinway, I abut the northern edges of the coverage zone. I begin to encounter numerous unbalanced empty stations, indicating riders are more likely biking out of this neighborhood than into it. This area also includes the docks that border LaGuardia Airport (LGA) though none can truly be said to provide convenient access. The question of access to LGA – and what manner of access – is the subject of intense contestation currently in New York City transit policy discourse. The administration of former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo proposed constructing an AirTrain from the Mets Stadium-Willets Point 7 station to LaGuardia Airport, while transit advocates clamored for a solution that brings public transit to the transit-starved neighborhoods in northern Queens.

This dock sits closest to LaGuardia airport, in the distance you can see an air traffic control tower. This certainly does not create any kind of realistic access for travelers though and I suspect very few riders use this dock to connect to the airport, credit: Gregory Suter.

Though the dock sits within eyesight of the air traffic control tower and road entering the airport, actually using the dock to catch a flight would involve a 30 minute walk to terminal B or a 40 minute walk to terminal C, effectively discouraging all but the most desperate and determined travelers. Despite an $8 billion renovation underway at the airport, the designs do not include space for secure bike parking or a Citi Bike dock at the terminals. Unless the New York state government commits to investing in transit infrastructure and micro mobility solutions as a means of accessing the airport, the hard edges surrounding LaGuardia will remain untraversable to all but vehicles.

TOXIC INFRASTRUCTURE PREVENTS WATERFRONT ACCESS

Having reached the northeastern terminus of my journey, I begin to arc back towards my start point at Hunters Point. The northern edge of the zone contains the hardest physical boundaries I’ve encountered yet; I ride on the sidewalk for safety from passing truck traffic. The severe edges here are hardened and reinforced by concrete walls running along 81st, designed to reduce noise from the nearby runways. Along 19th Avenue, fences close off Elmjack Little League Park as it undergoes renovation.

Suddenly, I approach the sign for Rikers Island; the foreboding road clearly unwelcoming for pedestrians or cyclists. Continuing along this stretch, I also pass a wastewater treatment plant and the massive Astoria Generating plant. Between these industrial and commercial facilities, over five miles of waterfront remains inaccessible for Queens residents. Piercing edges that separate residents from the waterfront represents a top planning goal in New York over the past two decades. As industry has withdrawn the city has converted many waterfront plots into accessible parkland such as Bushwick Inlet Park, Brooklyn Bridge Park, and Hunters Point.

WATERFRONT EDGES

I finally reached the western boundary along the East River about seven miles into the ride. Here, I find biker’s paradise: wide, two-way, separated paths snaking through Astoria Park, away from the violence of cars, offering beautiful views of Randall’s Island and the RFK bridge. For the first time during the ride, I am surrounded by other bikers, runners, and pedestrians, unsurprisingly considering the park space is designed for non-car activities. As I head south, I continue through a necklace of parks and green spaces all the while remaining on the same bike pathway. Though these neighborhoods face gentrification and high housing costs they also contain large public housing developments including NYCHA’s largest (Queensbridge Houses) which creates a cultural and class mixing throughout these waterfront parks.

The two-way bike lane provides a safe corridor along the east river for bikers, pedestrians, and runners. These parks provide incredible vistas of the Manhattan skyline and iconic infrastructure like the Queensboro Bridge, credit: Gregory Suter.

As I glide into the dock near my apartment, I reflect on my trip and the disparities and differences between neighborhoods and streets within my route. Clearly Citi Bike can offer so much: reliable transportation, connection to communities, access to parks and points of interest. But if the docks are not paired with effective infrastructure then the system falls short of its potential benefits.

Gregory Suter is a first year urban planning student. He aspires to use technology and data analytics to create more equitable and livable cities. He enjoys running and biking throughout NYC and constantly desires safer street infrastructure. Follow him on twitter @polarBearBiker.