NINA YOUNG

My arrival in Pittsburgh in 2016 coincided with the publication of Pittsburgh’s Affordable Housing Task Force’s Findings and Recommendations. One year later, in June of 2017, demolition of Penn Plaza’s 312 units of affordable housing in East Liberty began. This number represented a loss of 26% of affordable housing units in East Liberty, and upended the lives of over 200 people. One of these people was the father of Crystal Jennings, who was spurred to take action on his behalf. She became the main organizer for the Penn Plaza Support and Action Coalition. Crystal helped many residents with their moves. One day, I joined her, and we helped another former resident, Vivian Campbell, ready herself for her third move as the pandemic began last March.

The destruction of this apartment complex represented a speedy, disorienting event to neighborhood residents who had been steadily experiencing rising rents, the influx of an affluent population, and new storefronts and restaurants that they could not afford to frequent. This was not the first time that residents of East Liberty had been subjected to radical disruption. In 1966, the Urban Redevelopment Authority demolished 1200 homes as part of a plan to compete with the suburbs to attract shoppers. This urban renewal project was not as large as the one in the Hill District, Pittsburgh’s largest Black neighborhood, which displaced 8000 people.

Prior to moving to Pittsburgh, I photographed brownfields in the stage of mid-remediation, a stage that hinted at the possibility of a positive future. But here, my subject matter became landscapes of displacement, representing an erased future for the residents of the Penn Plaza Apartments.

Viewed through the lens of an urban planner instead of a photographer, these photographs taken in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh speak to the value of incorporating permanence into affordable housing policies for low and middle-income individuals and families in gentrifying neighborhoods.

HOMES

In her book Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It, Dr. Mindy Fullilove writes that a life of experiences, feelings, sounds and smells joins us to the buildings that provide us shelter.

Note the office of Duolingo, a Pittsburgh start-up that moved its offices to East Liberty in 2016. Google arrived prior in 2010.

REMAINS

When a person’s neighborhood is destroyed, they suffer through the traumatic stress of the loss of the working model of the world that existed in their mind.

NEW CONSTRUCTION: OFFICE SPACE AND RETAIL

“Homes not Whole Foods.” The Penn Plaza Support and Action Coalition gained a victory in 2017 when Whole Foods pulled out of being an anchor tenant in the proposed development. This victory was short-lived. In 2019, they rejoined the project.

ERASURE AND EXCLUSION

A judge ruled that LG Realty was legally entitled to build to 150 feet high. The City of Pittsburgh Planning Commission had voted 4-2 to approve the plan upon the condition that building heights be kept to 108 feet and that the plan include a community room in its development. The latter condition was considered a taking.

It is none too foreign a concept that marketers attempt to erase prior names of neighborhoods to make them appealing to new target demographics. Not even the name of a neighborhood seems to have permanence.

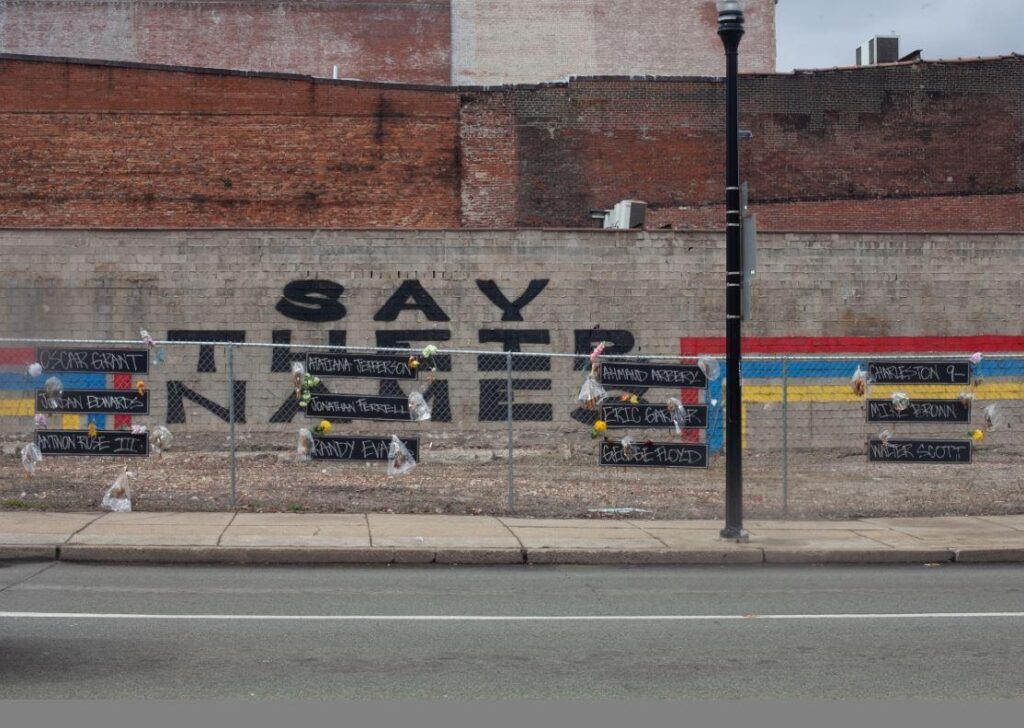

MEMORIAL

Memorials replace rebranding. A site of resistance.

A native New Yorker, Nina Young is a photographer, professor, and student pursuing the Master of Urban Planning at Hunter College. Her photographic interest in the built environment and its history has led her to focus on affordable housing. She holds an MFA from the School of Visual Arts and currently teaches at New York City College and BMCC.