MAX MARINOFF

In October 2020, the specter of winter in the pandemic loomed. As public parks that had been the social respite from isolation for many New Yorkers became less appealing with dropping temperatures and more and more businesses closed, Manhattan’s housing vacancy rate reached a 14 year high at 6.14% (16,145 empty units).1 Commercial real estate has fared even worse; as of December, almost 14% of midtown Manhattan’s office space is vacant, “the highest rate since 2009.”2 New York City is an attractive place to live in because it is vibrant and exciting, filled with culture, and its streets offer limitless exploration. However, during COVID, especially during the winter, for many the city somehow felt both empty and claustrophobic. The closure of entertainment venues and sudden limits on the city’s cultural offerings coupled with the freedom for many to work remotely have made city living less enticing and rural living more inviting for many New York City expats. The COVID-driven ubiquity of remote work and reports of limited reduction in productivity for many industries3— as well as the tremendous costs saved by employers not having to rent office space — foreshadow a potentially permanent shift in New York City’s commercial real estate landscape. And as commercial and residential real estate are interdependent, any dramatic change in the NYC commercial real estate market will impact NYC’s housing market. In a city that has seemed to have perpetually rising housing costs for the better part of three decades, how has and how will the sudden vacuum in Manhattan’s population and the cultural shift away from on-site work impact real estate in the city? Will housing costs finally go down? And if so, for whom?

Who Left?

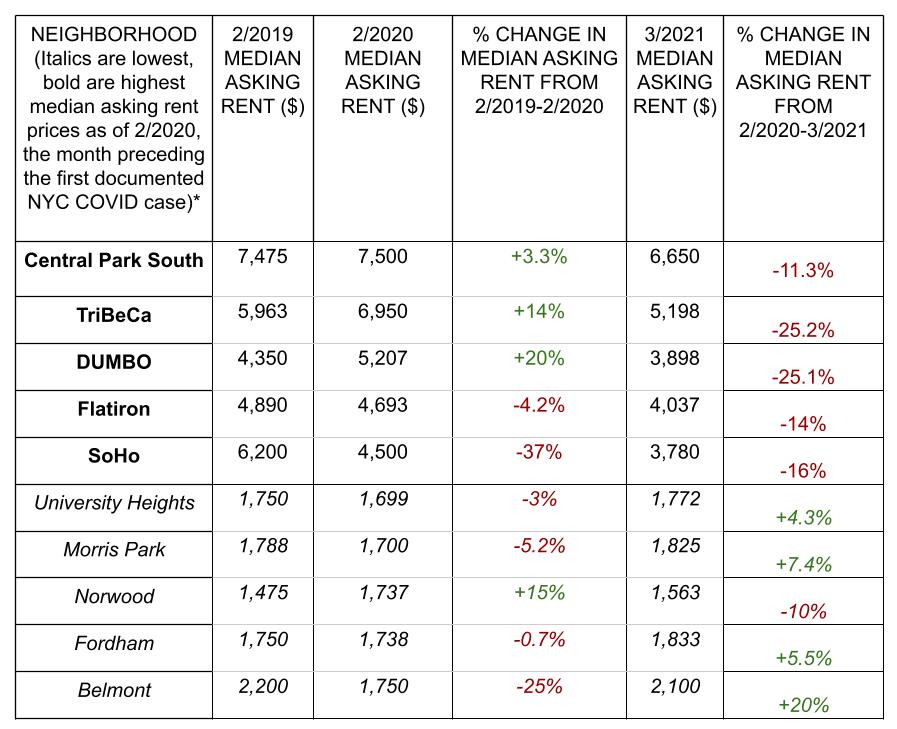

Those who left New York City could afford to, and most had jobs that allowed for remote work and an alternative place to live — either a second home, money to rent a second home or long term Airbnb, or family/friends to live with outside of the five boroughs. The median household income of the neighborhoods where more than 25% of people left the city in May was $119,125, and the median rent in those neighborhoods is $2,223.4 By contrast, in neighborhoods where less than 25% of the population left, the median rent is $1,414. This trend is also evident in StreetEasy data, which shows that the five neighborhoods with the highest median asking rents for February 2020 saw substantial increases in the number of rental vacancies by March 2021.5 A sudden rise in vacancies in any neighborhood is likely to cause rental prices to go down due to the laws of supply and demand.6 And as expected, this phenomenon of decreasing rents is evident in the current rental prices in the most expensive NYC neighborhoods, as detailed in Figure 1. The most expensive New York City neighborhoods did not just drop in the rental price; they dropped precipitously, with two previously expensive neighborhoods’ median asking rents dropping by as much as 25% from February 2020 to March 2021.

*Although Bronxwood was listed as the lowest median asking rent, StreetEasy did not have data for this neighborhood for most months between 2020-2021. For this reason, I excluded Bronxwood from the dataset. It is also worth noting that StreetEasy data is accrued from rent listings on the web. This excludes properties that may be listed informally; by word of mouth, or flyers.

Source: Street Easy Data Dashboard7

Financial Impact of Remote-Work Prevalence for NYC

In addition to the exodus of city residents during the pandemic, falling asking rental prices could also be influenced by the fact that many vacant units’ proximity to offices may now be an irrelevant feature. Various factors influence a neighborhood’s rental prices, including access to public transportation; access to commercial amenities, such as bars, restaurants, and entertainment venues; quality of housing stock; and even intangible attractions like trendiness. However, another significant determinant of residential rents is the units’ proximity to jobs, their distance from business districts, or “economic focal points.”8 The neighborhoods with the top five pre-COVID median asking rents (see bolded names in Figure 1) all share proximity to some of the city’s densest business and commercial districts. Central Park South is near Midtown, TriBeCa is near the Financial District, DUMBO is near Downtown Brooklyn, Flatiron is near both Lower and Midtown Manhattan, and SoHo is near the Financial District. The pattern of high rents in and around business districts and decreasing rent prices with increasing distance from the city center is known as the “bid-rent function.”9 Post-lockdown, as remote work became more prevalent, the most expensive NYC neighborhoods to rent in no longer had the asset of being close to jobs, and the “bid-rent function” was increasingly moot. If enough employers permanently embrace the remote-work model, the concept of a “business district” may become an archaic feature of cities. The remote-work model also has obvious implications for commercial real estate since companies that have moved their labor force to remote work are considering letting their long-term leases expire. Even before many of these 7 to 10 year commercial leases have expired, the market value of office towers in Manhattan has fallen by 25% resulting in an expected $1 billion loss in property taxes for the city.10

Lack of Affordable Housing May Worsen

While the most expensive New York City neighborhoods dropped in asking rental prices, the least expensive neighborhoods did the opposite. According to the same StreetEasy dataset, four out of five city neighborhoods with the lowest pre-pandemic median rental asking prices saw their median asking rents increase. For comparison, before the pandemic, these same four neighborhoods’ median asking rent prices decreased from February 2019 to February 2020. The graph below in Figure 2 shows the monthly means of the top five neighborhood median asking rent prices against the monthly means of the bottom five neighborhood median asking rent prices from February 2020 through the pandemic. As previously expensive neighborhoods’ rents plummet, the less expensive areas see a slight rise in rental prices.

The implication of falling rents at the high end of the housing market and slightly increasing rents at the lowest end is that affordable housing may become even more scarce, contrary to what the rise in vacancies city-wide might have suggested.12 One reason for this scarcity in affordable rentals is that the increased supply of housing at the top end of the market remains unaffordable for most people. NYC’s highest rents were so prohibitively expensive for those with modest to median incomes that even 25% drops in asking rent prices still keep many of these units outside the range of affordability for many New Yorkers.

For example, if a family of three making the AMI were to rent in DUMBO — which is the lowest among the five neighborhoods with the highest median asking rents — they would be paying 42% of their income on rent, well above the 30% threshold for a household to be considered rent-burdened. It is important to note that the rent burden would likely be even greater for a NYC family, since the current AMI controversially includes wealthier Rockland, Putnam, and Westchester counties13. At the same time that the highest asking rents remain unaffordable despite their steep drop, the property tax assessments for these units, which are partially drawn from their asking rents,14 have decreased. Property taxes are “the largest source of city revenue.”15 The combination of falling residential property values in the city’s most expensive neighborhoods and the decrease in market commercial real estate values spell a significant loss in tax revenue. Potential austerity measures to bridge this budget gap, such as cuts to municipal social welfare programs and the scaling back of urban infrastructure projects, will limit resources for the most vulnerable New Yorkers.

The rising rents of New York City’s least expensive rental units may increase more sharply as remote work continues and amenities such as apartment size become a priority over proximity to work for those seeking housing. The lower rental costs in these areas could also draw potential renters for whom commuting time is no longer a concern. According to a study on the impact of remote work prevalence in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, “residents move to the periphery. The largest driver of this effect is workers who previously had to commute but can now work from home. They tend to move farther away from the urban core to locations with more affordable housing.”16 As demand increases in neighborhoods with lower asking rents, these “locations with more affordable housing” may no longer be affordable. As it stands, many currently living in these neighborhoods are at risk of displacement. In 2018, the five New York City neighborhoods with the highest percentage of residents living in poverty were Fordham and University Heights, Highbridge and Concourse, Morrisania and Crotona, Belmont and East Tremont, and East New York and Starrett City.17 Three of these neighborhoods — Fordham, University Heights, and Belmont — saw their median asking rent prices increase in the year since NYC’s first reported COVID case. If “periphery” neighborhoods like these continue to become more expensive and the highest rents remain unaffordable despite their steep drops, many of the city’s lowest-income residents face the threat of being priced out of all five boroughs.

Notes

1. Michael Kolomatsky, “A Manhattan Rental Recovery,” The New York Times, November 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/19/realestate/manhattan-rental-recovery.html.

2. Matthew Haag and Dana Rubenstein, “Midtown is Reeling? Should its Offices Become Apartments?” The New York Times, December 11, 2020.

3. Julian Birkinshaw, J. Cohen, and P. Stach, “Research: Knowledge Workers are More Productive from Home,” Harvard Business Review, August 31, 2020,

4. Kevin Quealy, “The Richest Neighborhoods Emptied Out Most as Coronavirus Hit New York City,” The New York Times, May 15, 2020.

5. StreetEasy, “StreetEasy Data Dashboard,” Rentals in NYC, Rental Inventory, all Bedroom Count, Accessed May 1, 2021,

6. Jerusalem Demsas, “COVID-19 Caused a Recession. So Why Did the Housing Market Boom?” Vox, February 5, 2021, https://www.vox.com/22264268/covid-19-housing-insecurity-housing-prices-mortgage-rates-pandemic-zoning-supply-demand.

7. StreetEasy, 2021.

8. G. Stacy Sirmans and John D. Benjamin, “Determinants of Market Rent,” The Journal of Real Estate Research, vol. 6, no. 3, 1991: pp. 357–379. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44095552.

9. Arpit Gupta, J. Peeters; V. Mittal, and S. Van Nieuwerburgh, “Flattening the Curve: Pandemic-Induced Revaluation of Real Estate,” VoxEU, CEPR, February 11, 2021.

10. Matthew Haag and Peter Eavis, “After Pandemic, Shrinking Need for Office Space Could Crush Landlords,” The New York Times, April 8, 2021.

11. StreetEasy, 2021.

12. Caroline Spivack, “Rents are Down in Manhattan but up in Neighborhoods Hit Hardest by COVID-19,” Curbed, New York, September 11, 2020, https://ny.curbed.com/2020/9/11/21430634/nyc-rentals-manhattan-queens-bronx-rent-prices.

13. Kay Dervishi, “Why AMI are the three most controversial letters in New York City housing policy,” City and State, NY, August 13, 2018, https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/policy/housing/new-york-city-area-median-income-housing-policy.html.

14. Haag and Eavis, 2021.

15. Haag and Dana, 2020.

16. Matthew Delventhal, J.; E.Kwon and A. Parkhomenko, “How Do Cities Change When We Work from Home?” USC Lusk Center for Real Estate, December 4, 2020,

17. NYC Health, “NYC DOHMH Community Health Profiles, 2018,”

Max Marinoff is a lifelong New Yorker who currently works at the FDNY. He has a passion for NYC life and culture, particularly the local communities that give the city its texture and vitality. A former NYC tour guide, he is well versed in the city’s history, lore, and idiosyncrasies.